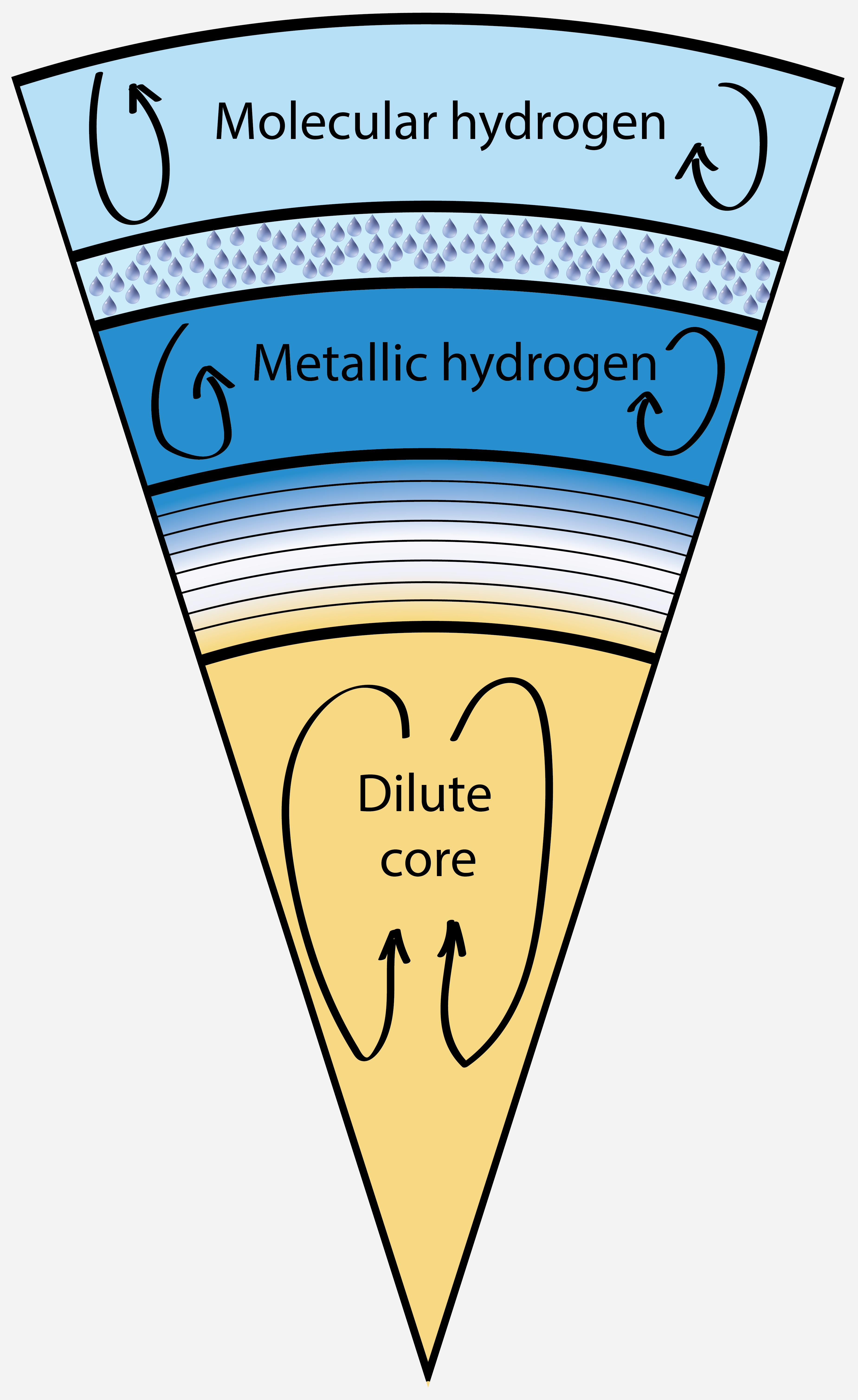

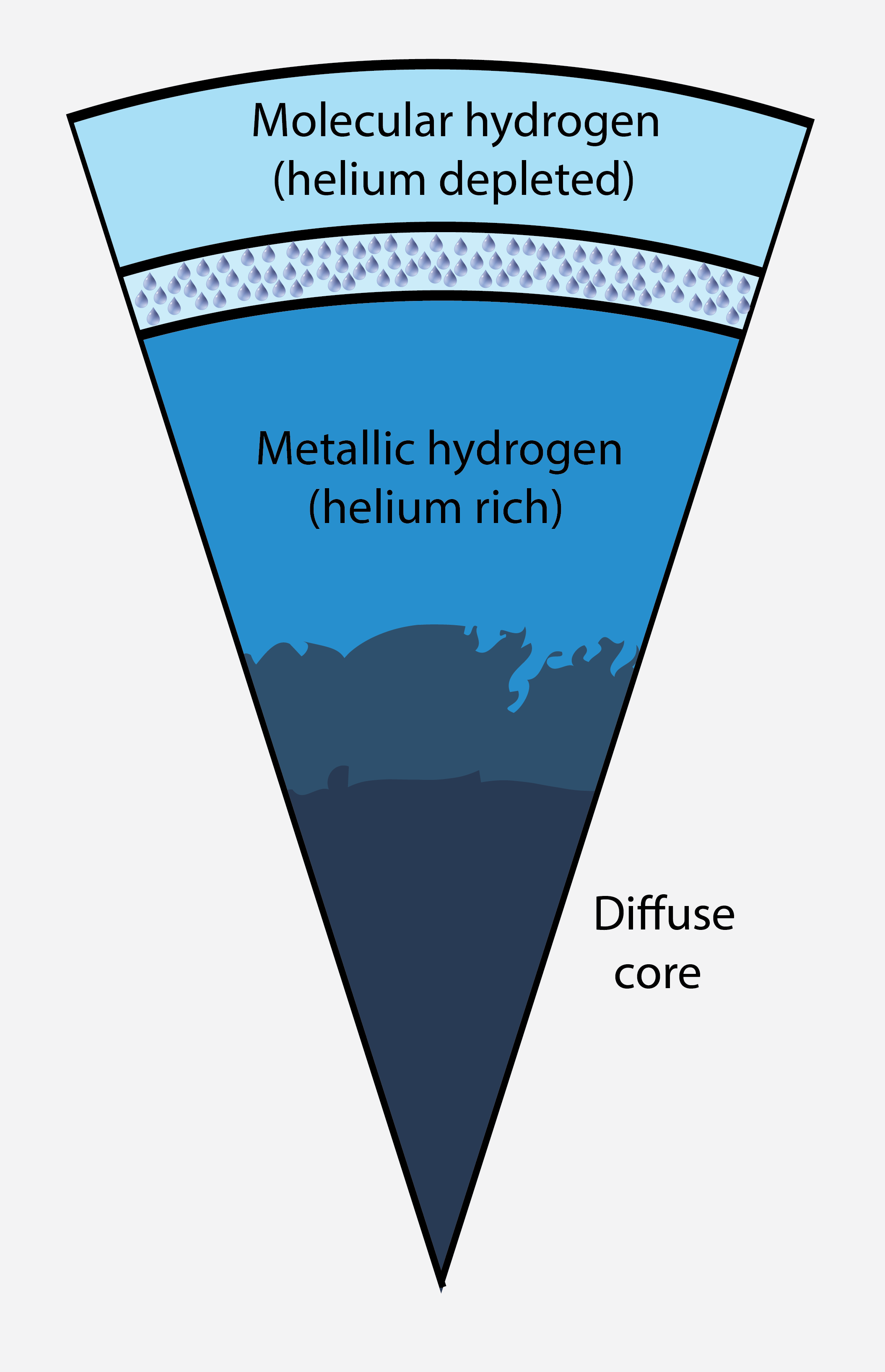

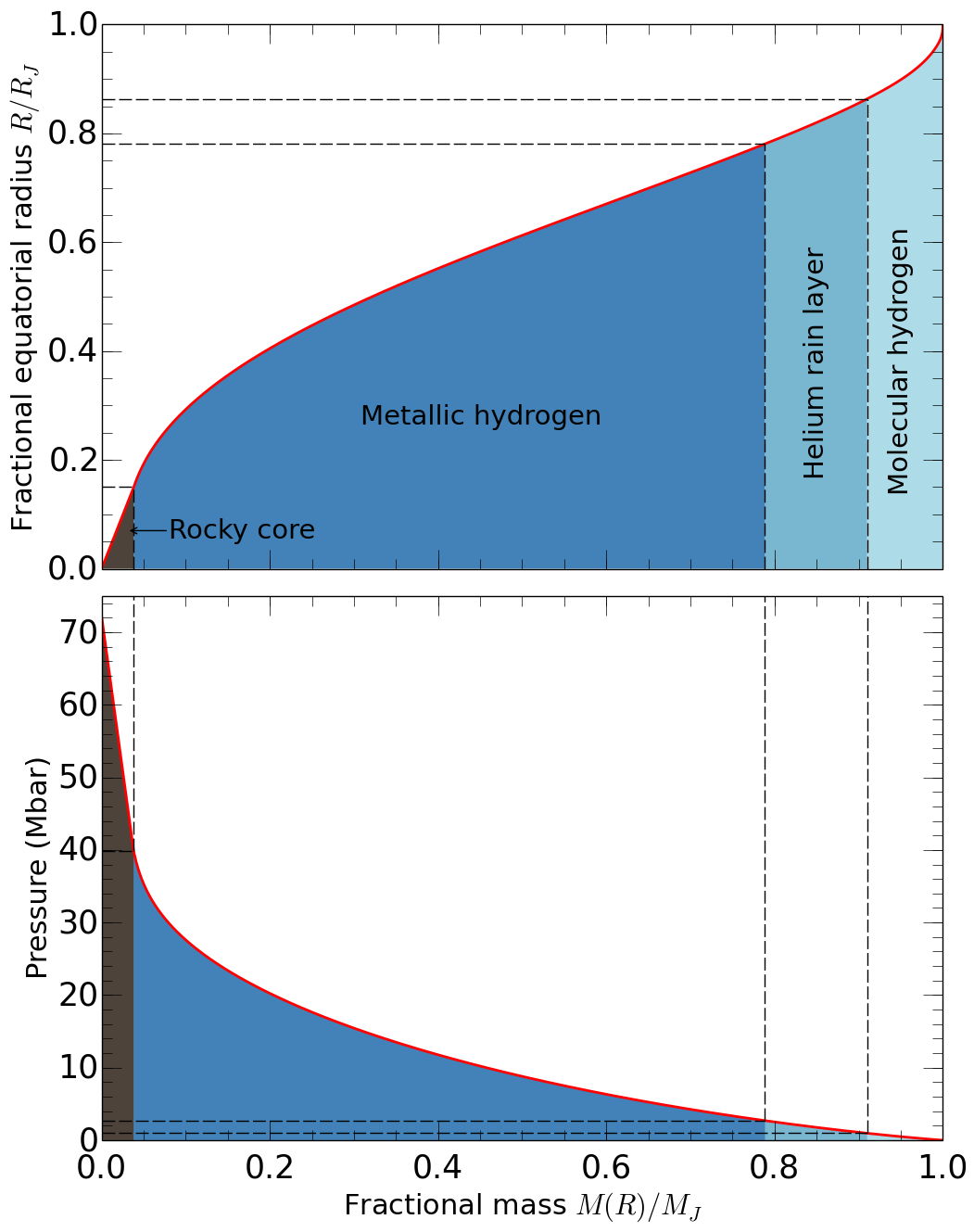

Jupiter's interior structure with helium rain layer and dilute core.

|

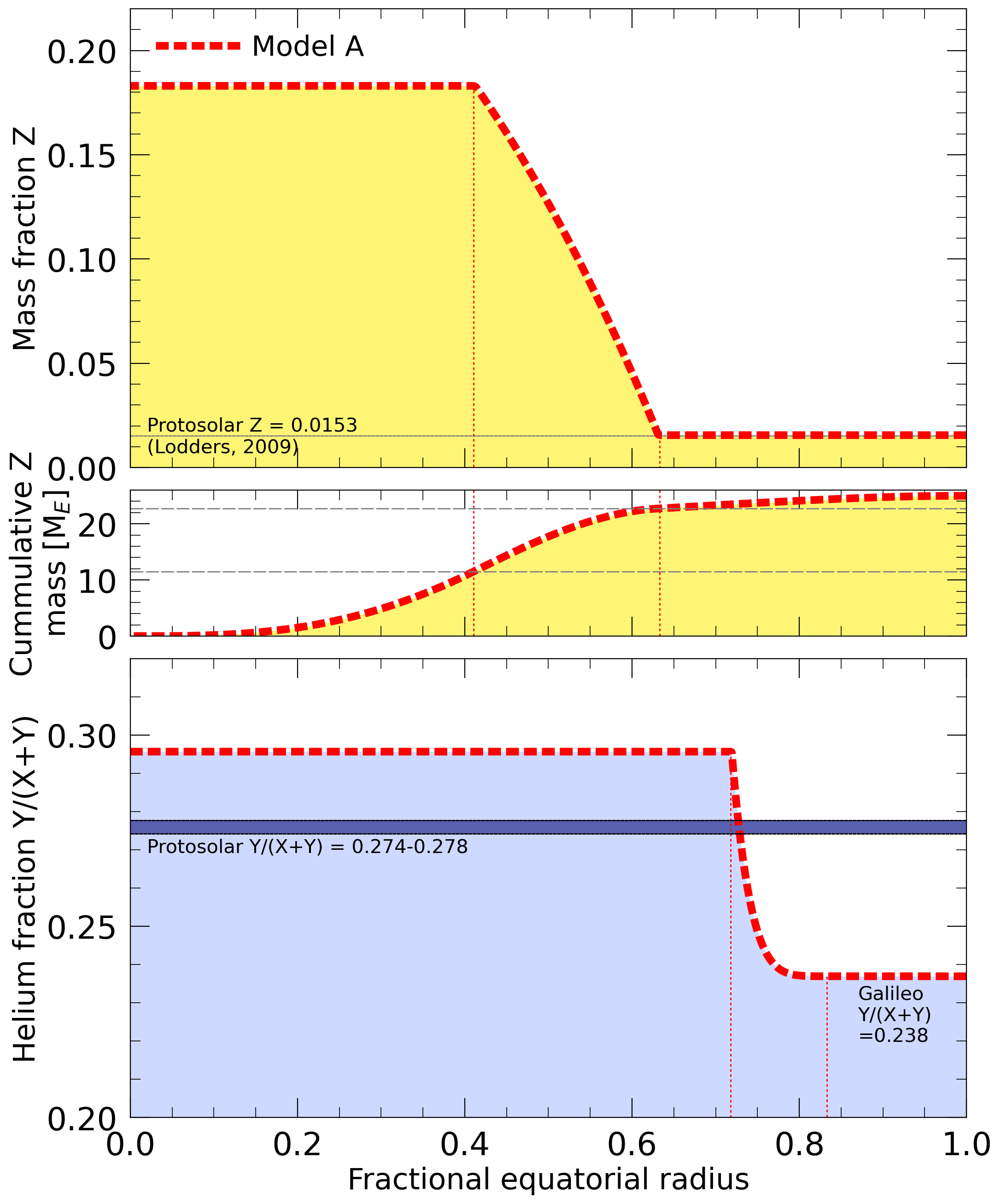

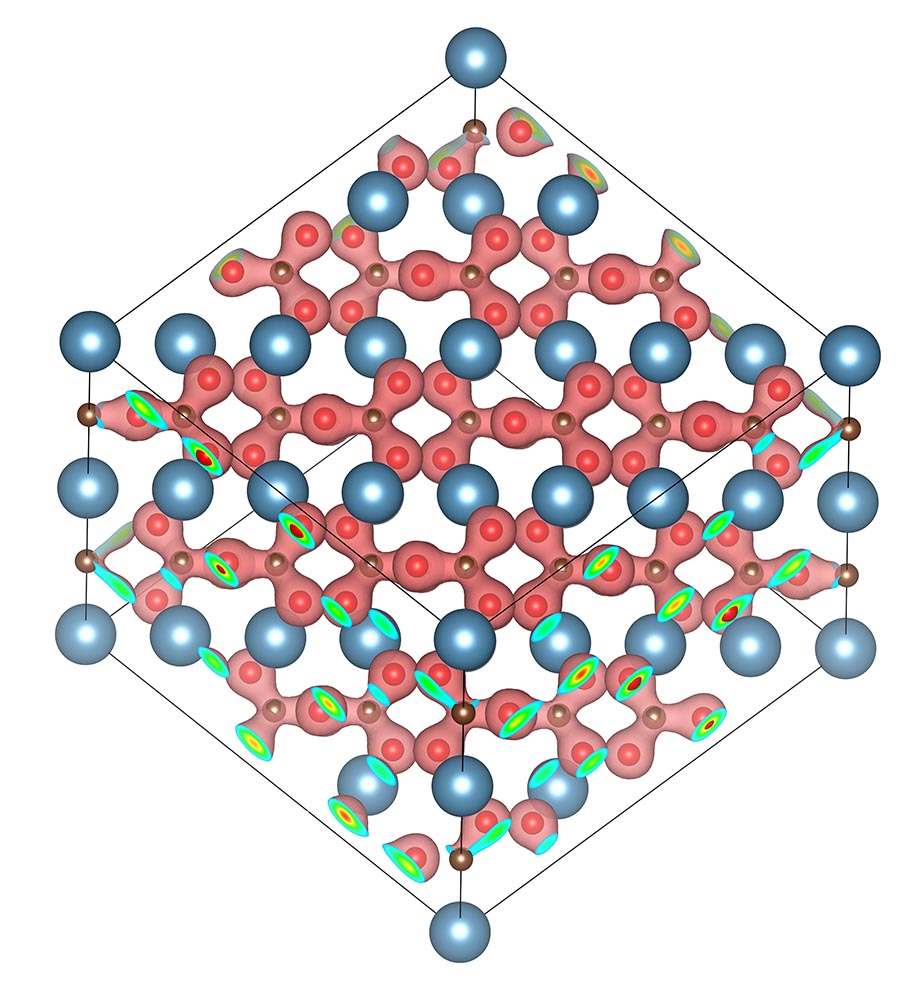

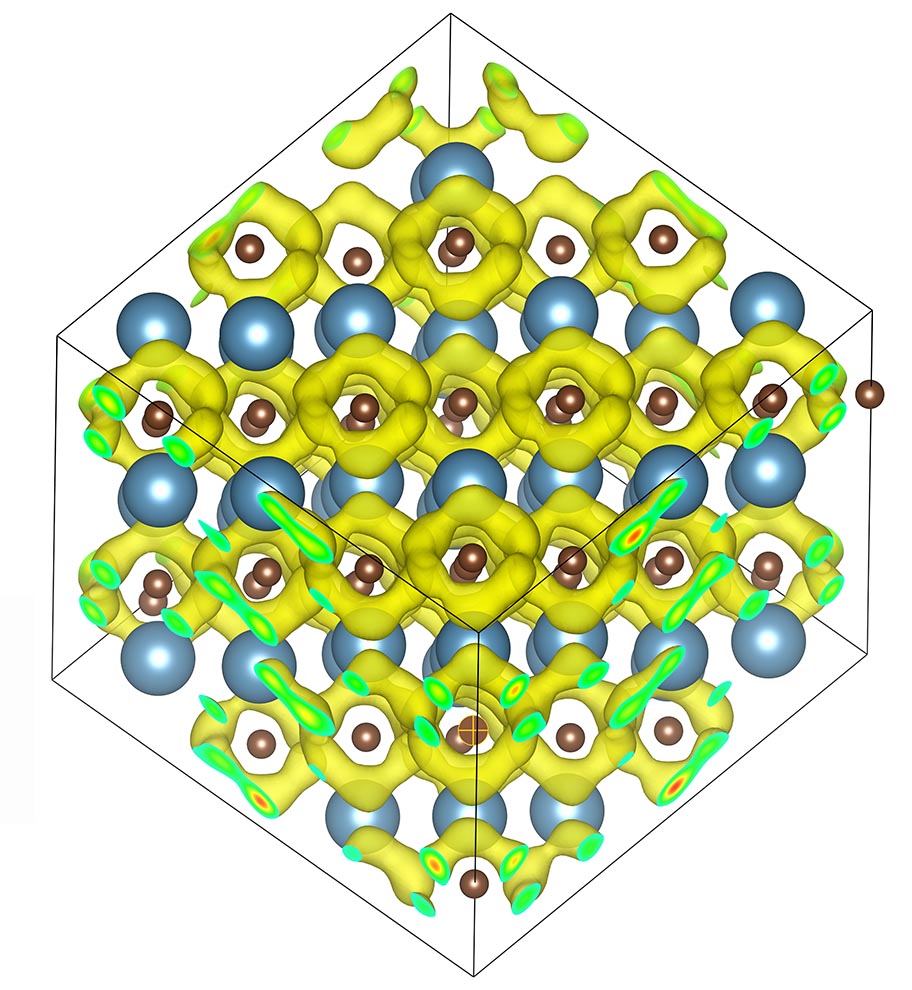

Heavy element (upper panel) and helium mass fractions (lower panel).

|

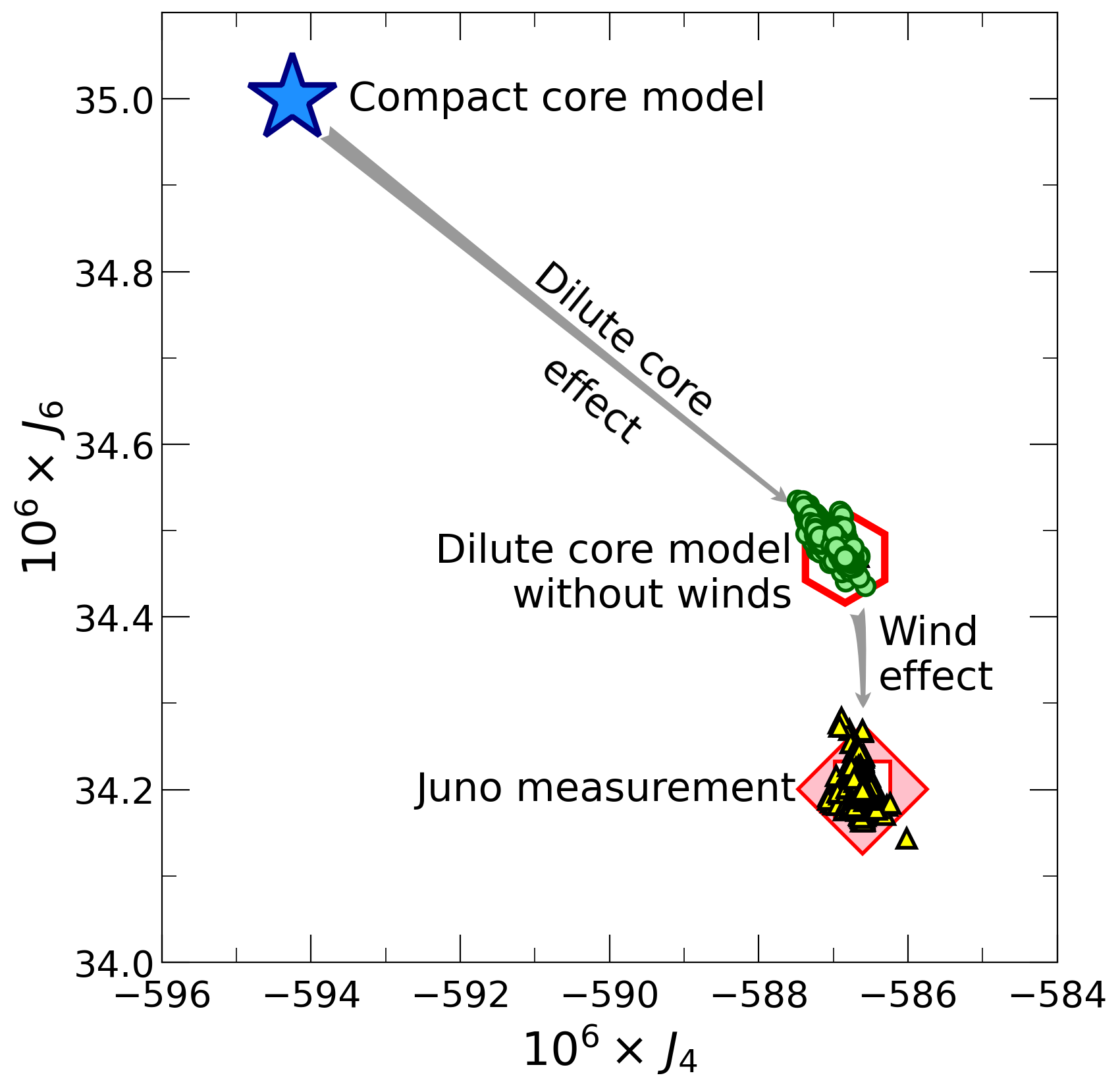

Gravity harmonics J4 and J6 measured by the Juno spacecraft (red diamond) and predicted from models (all other symbols).

|

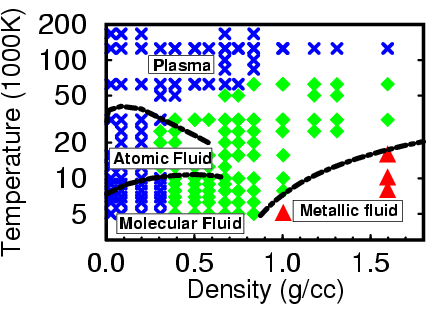

The Juno spacecraft measured Jupiter's gravity field with exquisite

precision. Matching the measurements with interior models that also

agree findings by the earlier Galileo entry probe and make

physical assumptions about the properties of hydogen-helium mixtures

has been a real challenge. In our latest article, we satisfy

Juno and Galileo measurements for the first time by

constructing Jupiter models with a large dilute core that

extends to 60% of the planet's radius (left and middle panels). We

predict the dilute core to be comprised of 58% hydrogen, 24% helium,

and only 18% of heavier elements. The dilute core reduces the magnitudes of

the gravity harmonics J4 and J6 (right panel) so

such an extent that we can match the spacecraft measurements with wind

models that we optimize simultanesouly with model parameters for the

interior. Our dilute core is homogeneous and convective. So we predict

it to contribute to the generation of Jupiter's magnetic field in

addition to the metallic hydrogen layer. Having two interacting dynamo

layers may help explain the structure of Jupiter's magnetic field.

|

|

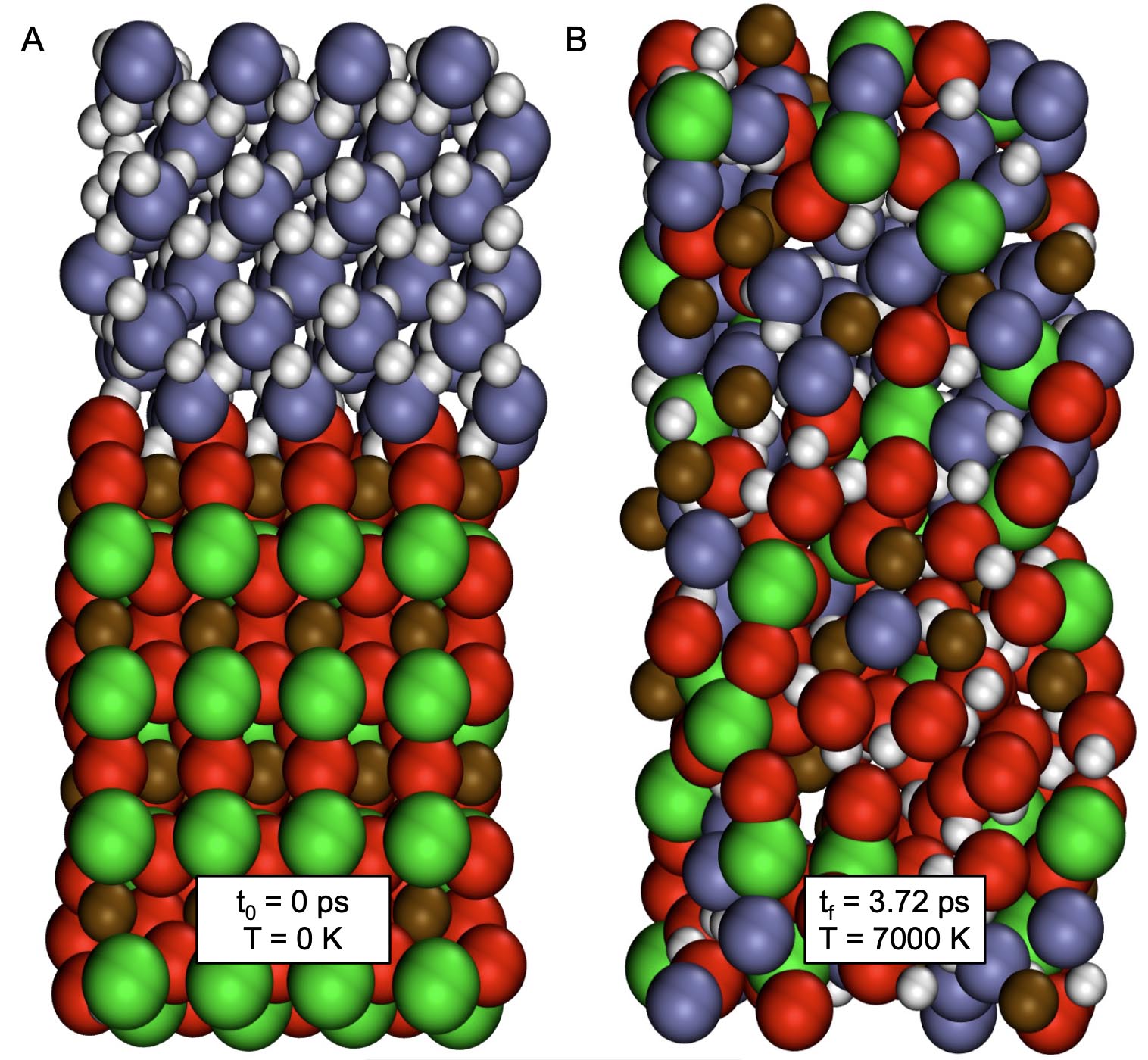

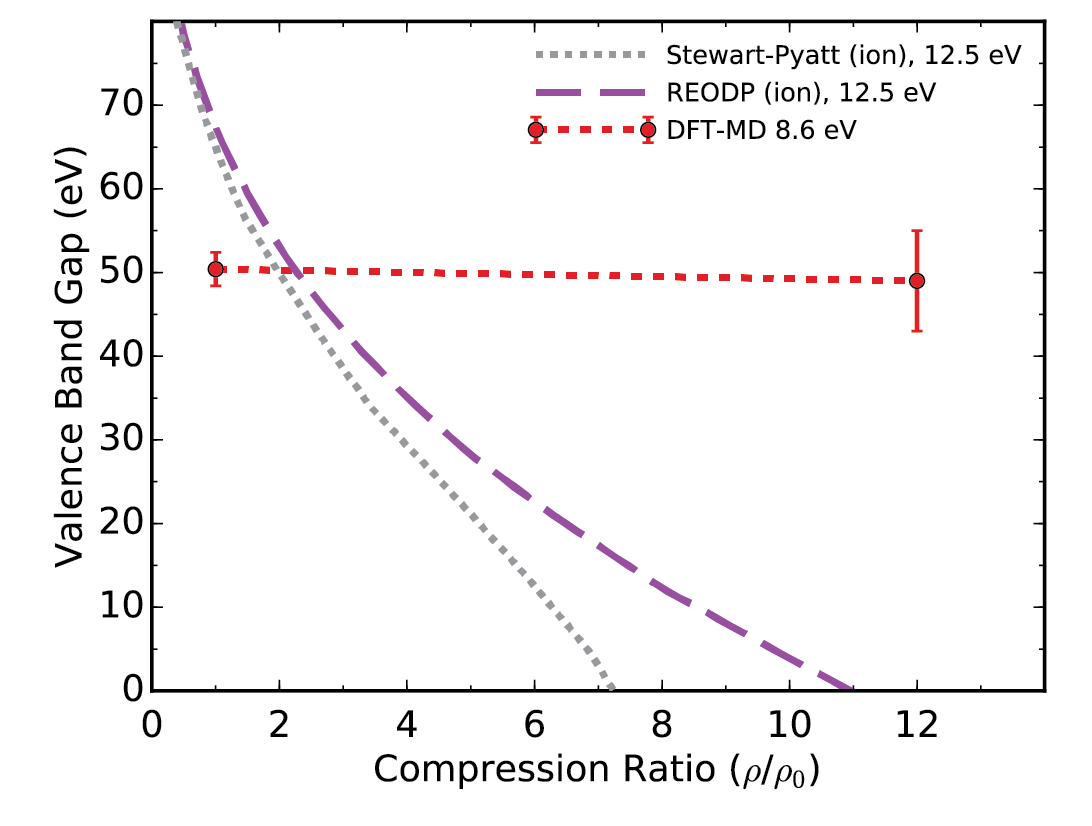

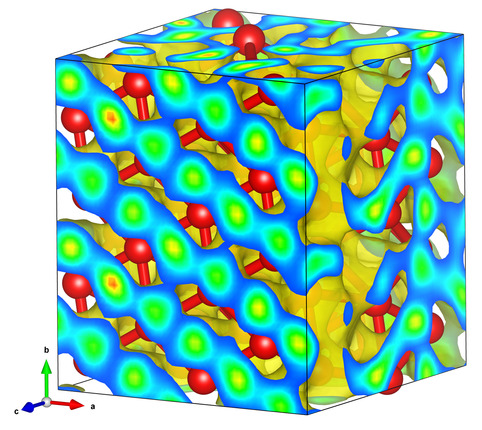

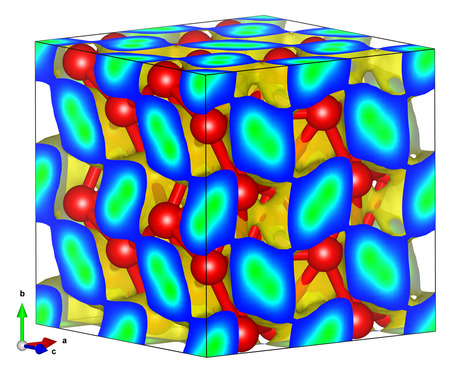

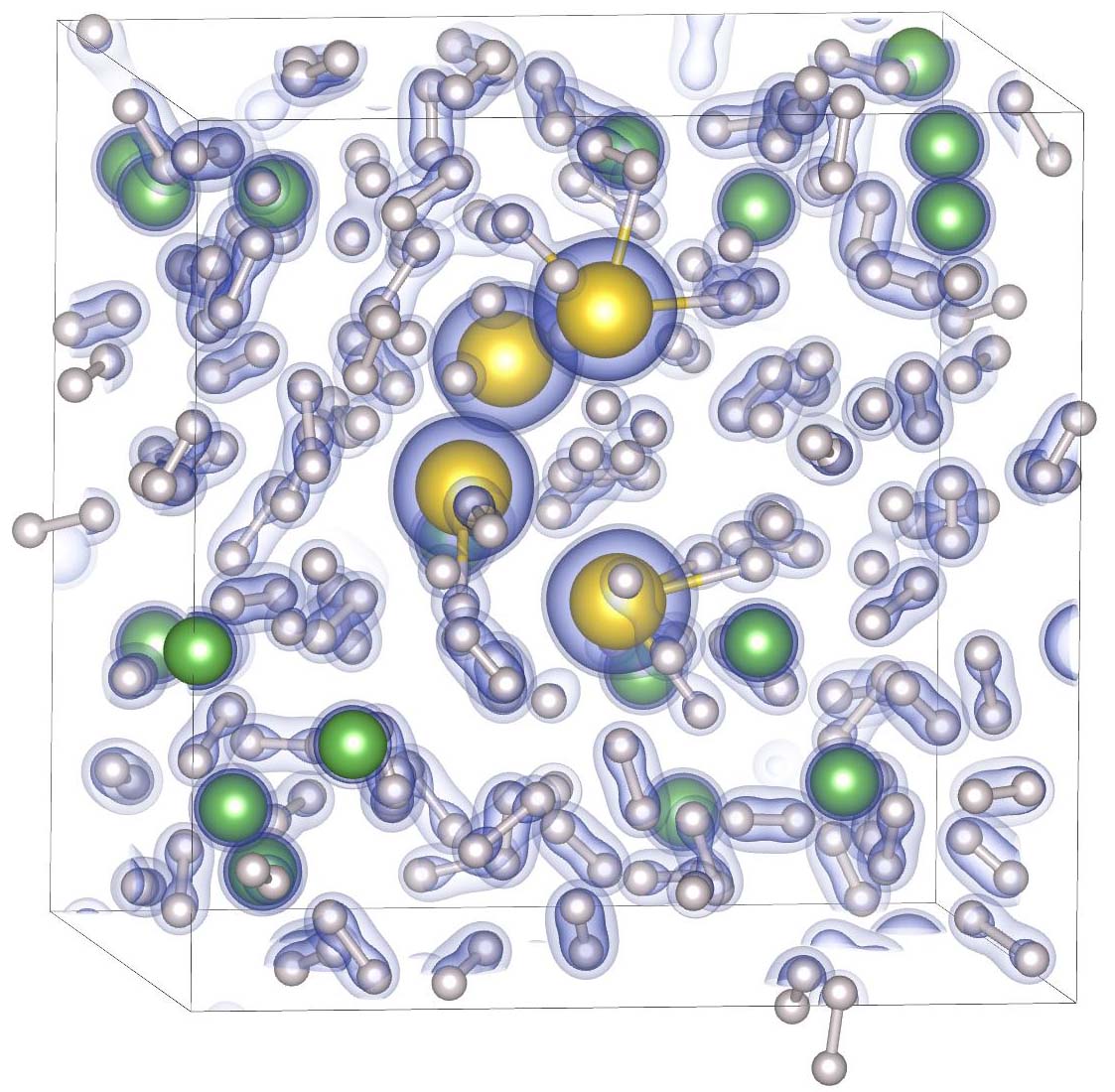

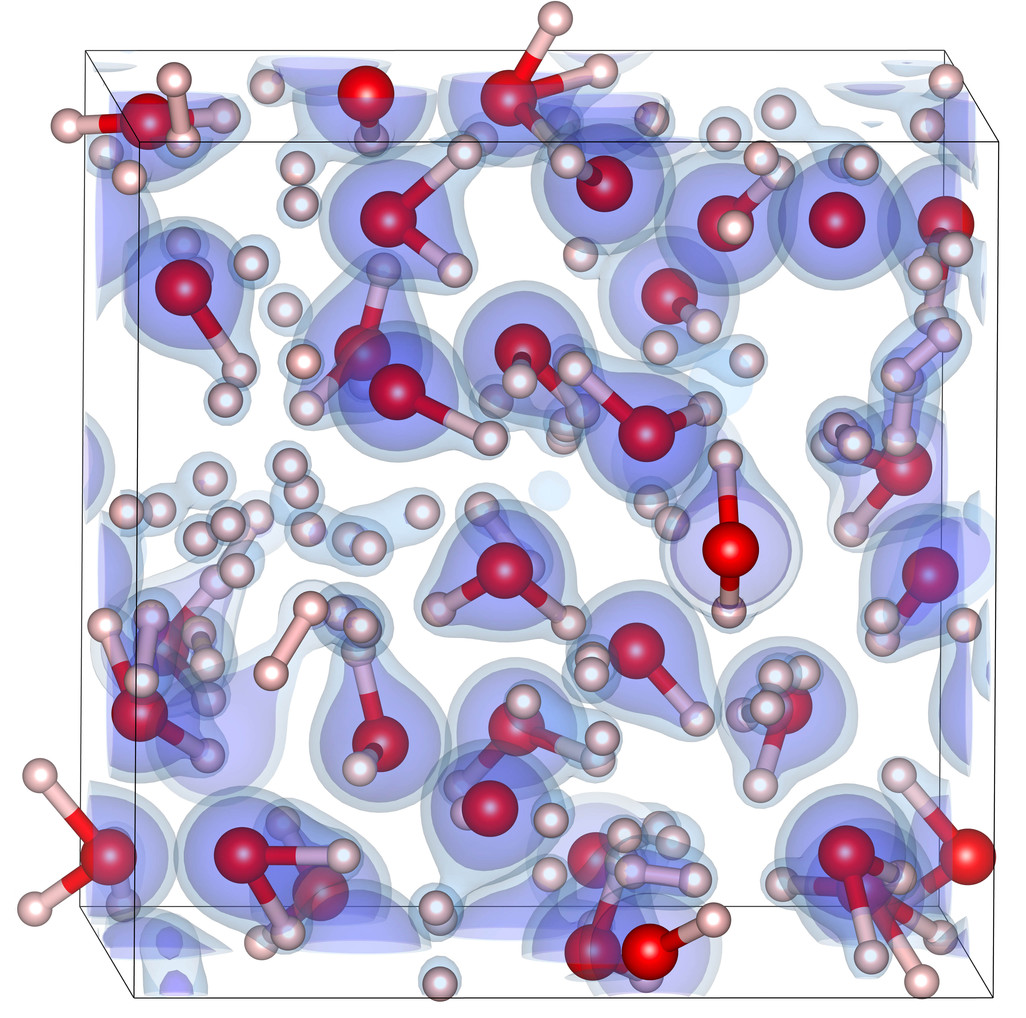

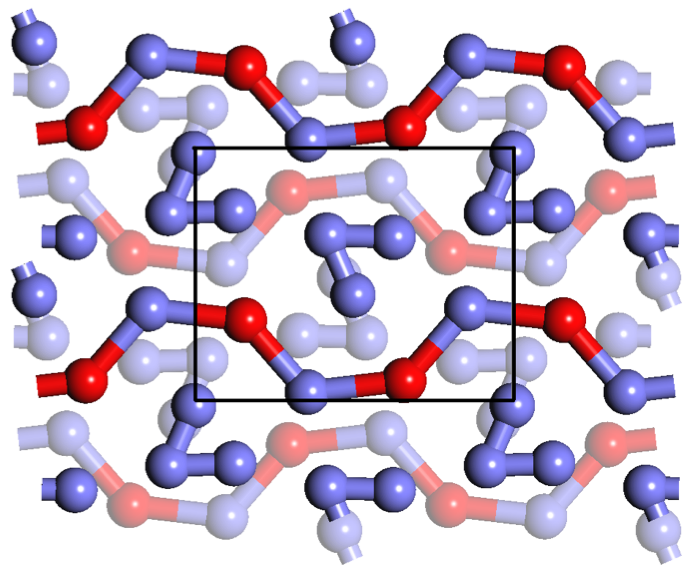

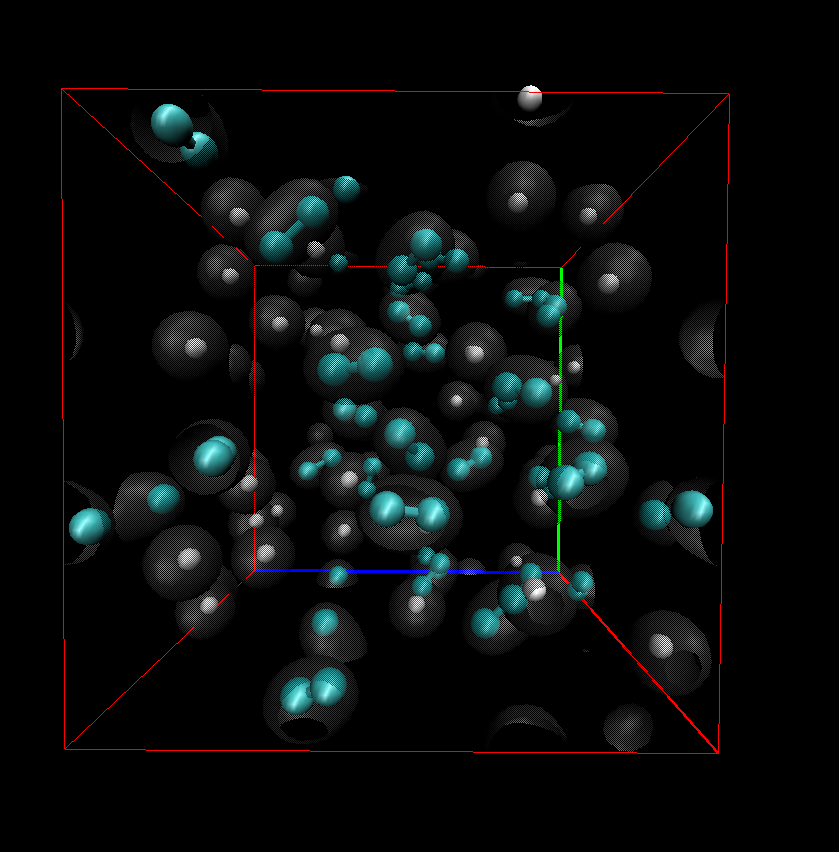

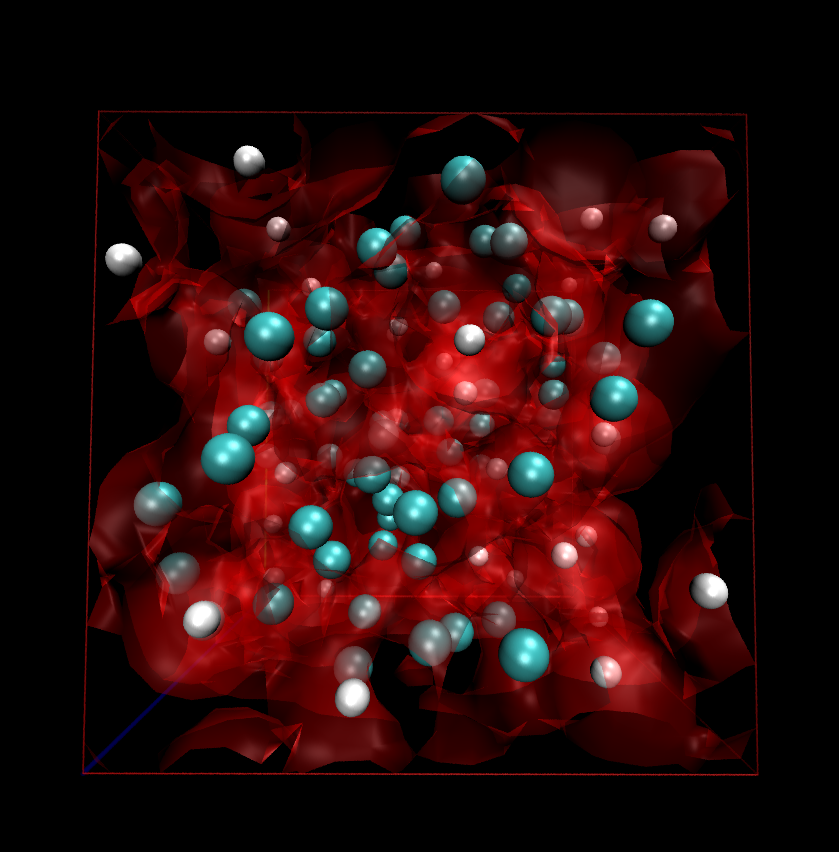

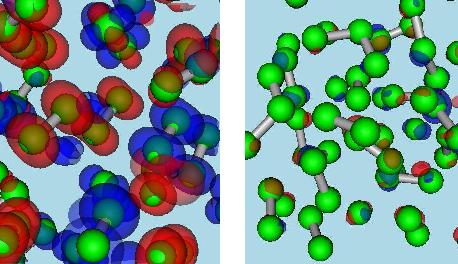

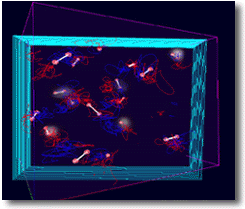

Initial and final configurations of ab initio simulations of rock-ice mixtures.

Initial and final configurations of ab initio simulations of rock-ice mixtures.

|

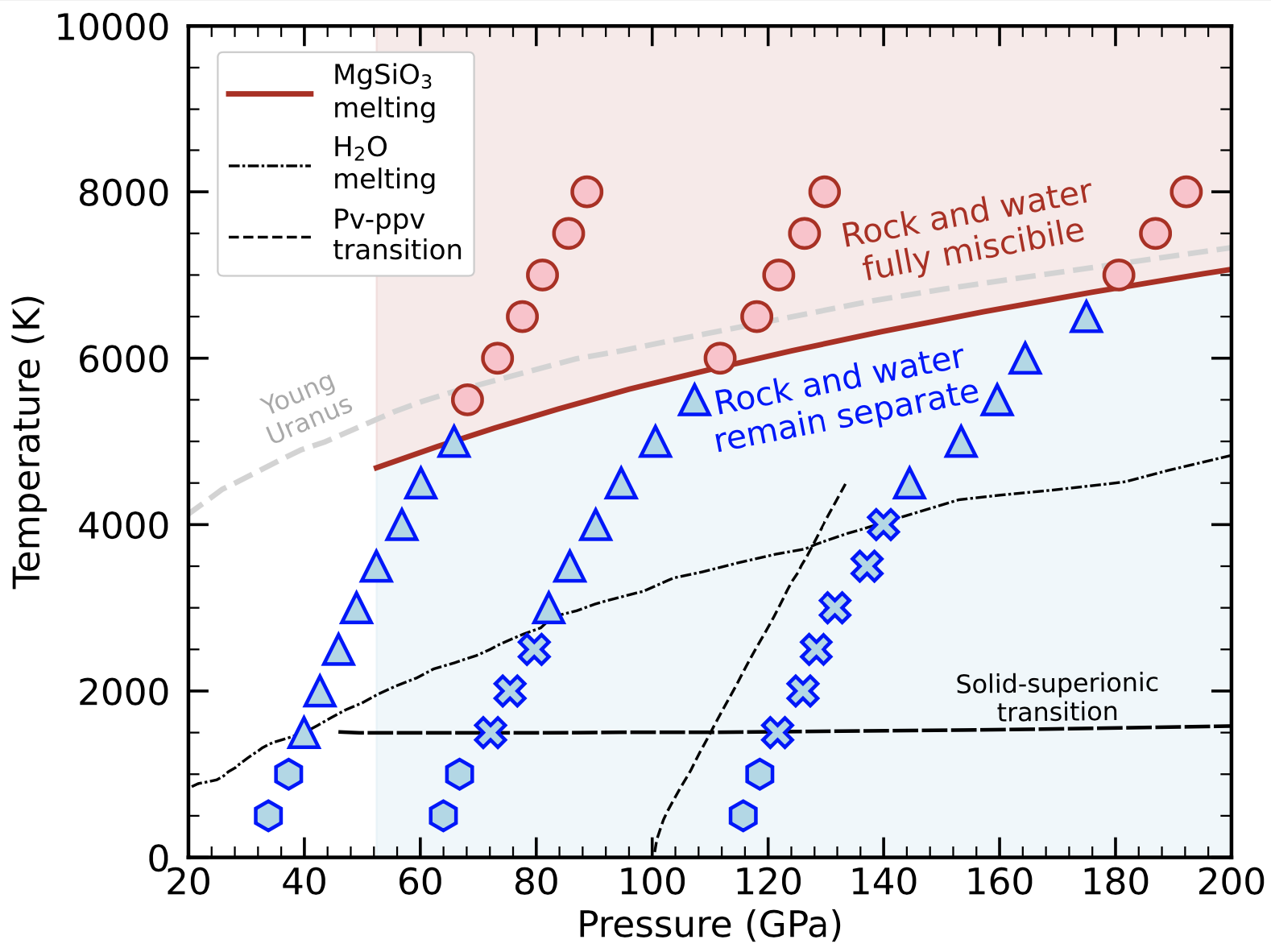

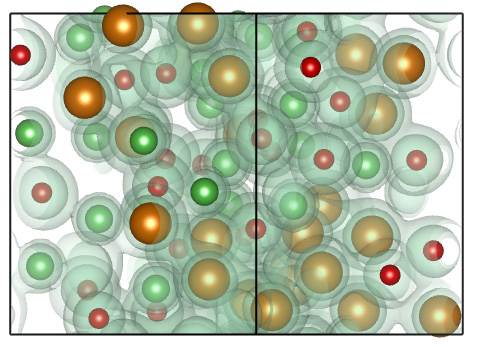

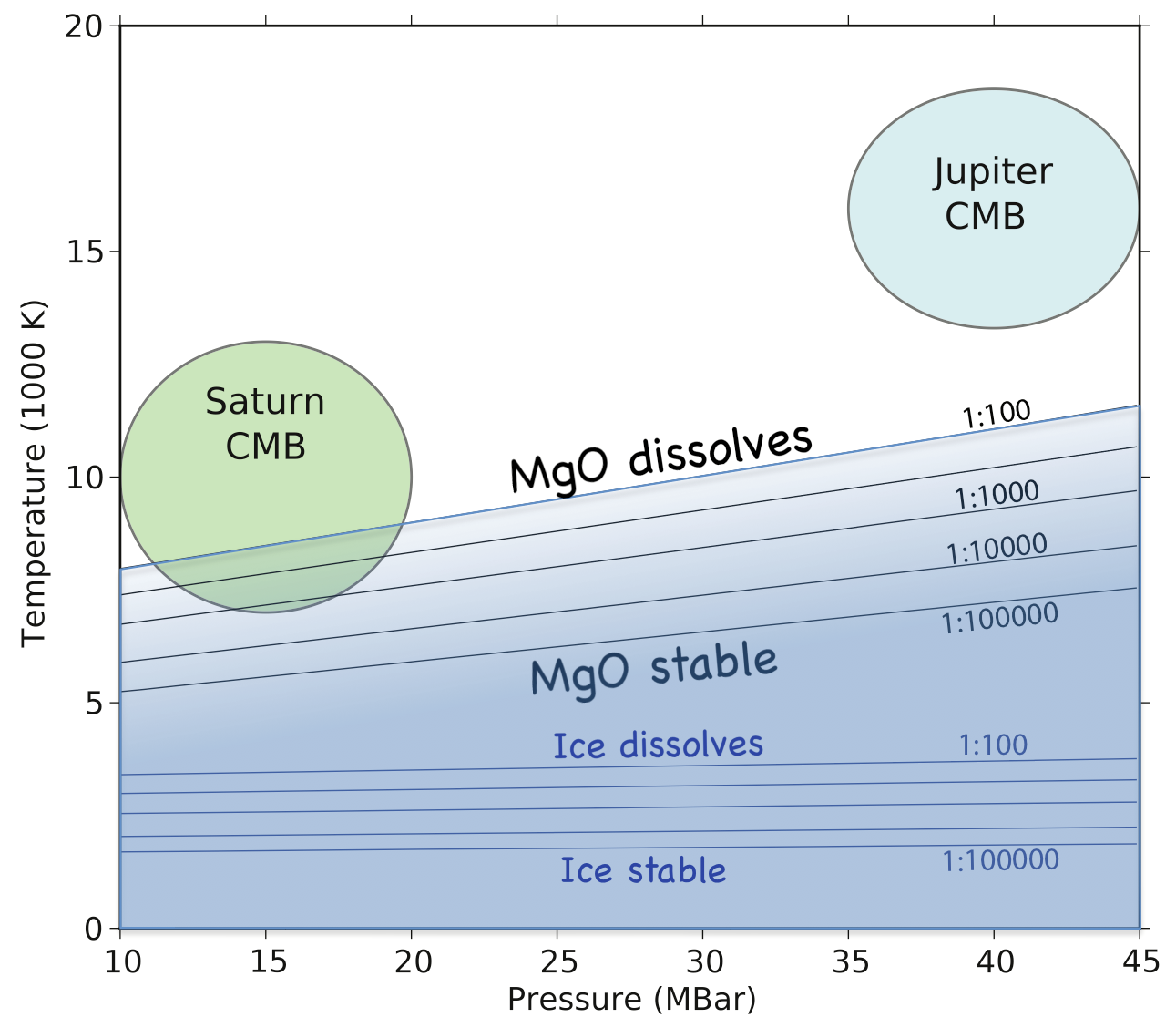

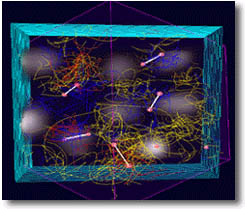

Pressure-temperature conditions where rock and ice remain separate (blue) or mix (red) in all proportions.

Pressure-temperature conditions where rock and ice remain separate (blue) or mix (red) in all proportions.

|

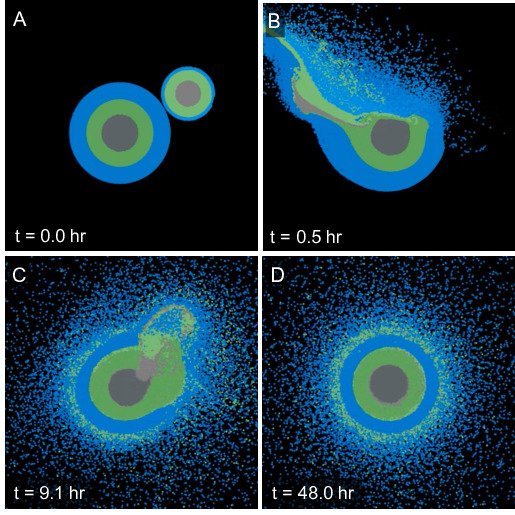

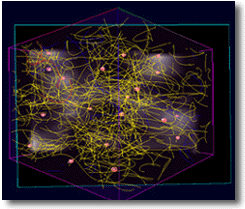

Simulation of planet size imacts illustrating that rock and ice mix dynamically.

Simulation of planet size imacts illustrating that rock and ice mix dynamically.

|

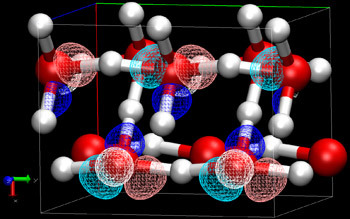

In our latest article, T. Kovacevic, F. Gonzalez-Cataldo, S. T. Stewart, and I study conditions in the interiors of water world planets that are expected to contain large amounts of rock and ice. We focus on the question whether they have well separated layers or rock and ice or if they likely have mixed rock-ice layers. First we performed ab initio computer simulations (upper left diagram) and determined rock and ice mix in all proportions as soon as the temperatures become sufficiently high for rock to melt (upper center). Finally we perform planet-size impact simulations (upper right) with the SPH method to demonstrate that such conditions are reached when giant impacts occur during a planet's formation. We conclude of water world planets likely have mixed layer when they form but it yet remains to be determined how long such layers last.

|

|

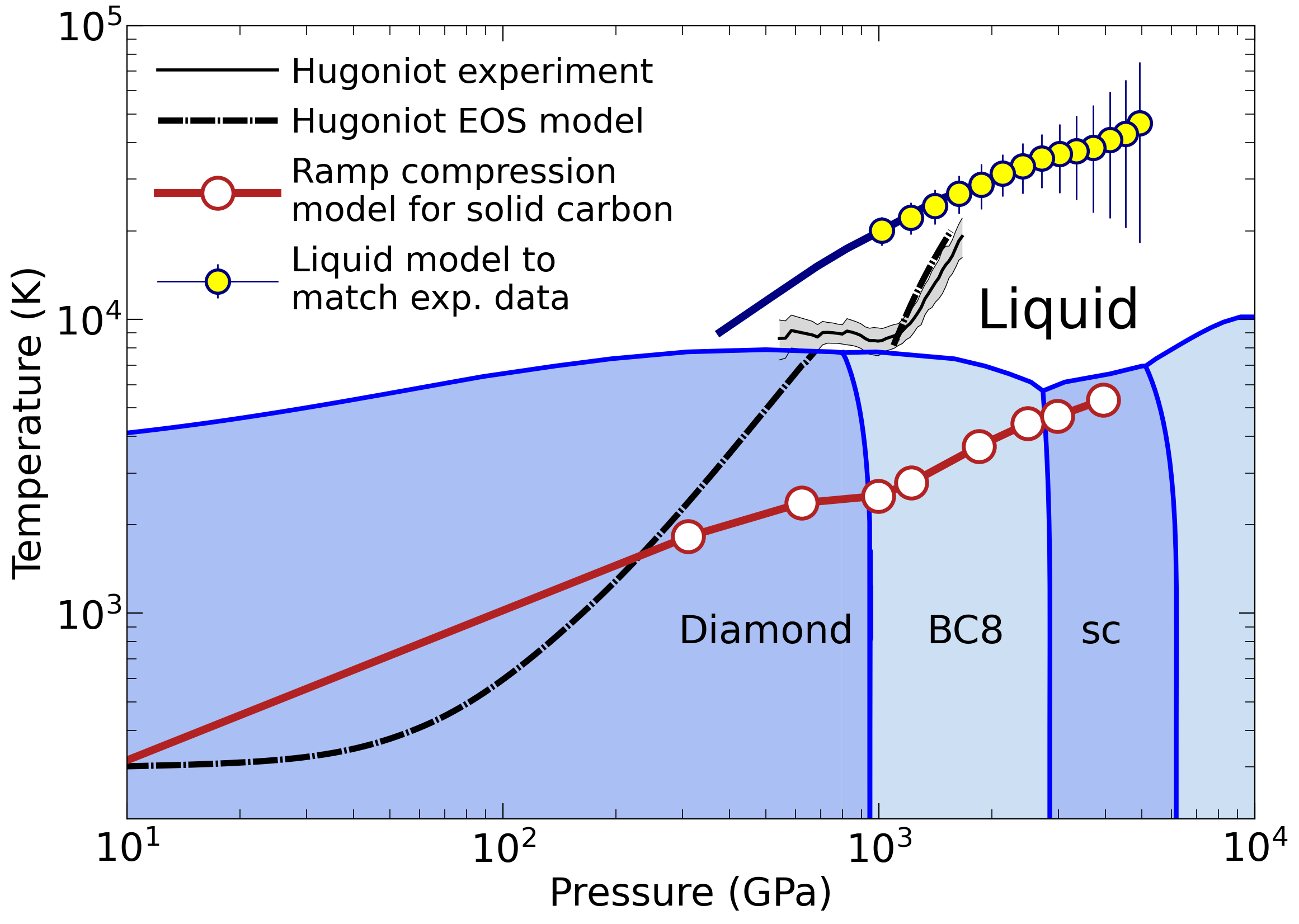

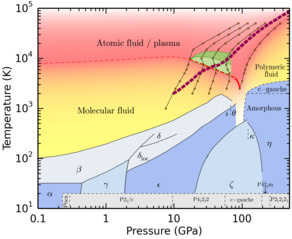

Phase diagram of carbon with liquid and solid model for ramp compression experiments

|

In our latest article, F. Gonzalez-Cataldo, B.K. Godwal, K. Driver, R. Jeanloz, and I study with computer simulations a material becomes during ramp compression experients. The work was motivated by the ramp compression experiments on diamond by R. Smith et al. that reached stress conditions of several tera Pascals. We found that for a given density, the measured stresses were too high to be compatible with results from ab initio simulations. The measured density-stress point can be matched with simulation results of liquid carbon (yellow symbols). This assumes the diamond samples melted during compression, which is under debate. There was sufficient energy in the experiment for this occur but no evidence for it was collected during the measurements. Later experiments by A. Lazicki et al. demonstrated that carbon remained solid.

So we derive a multi-step model for ramp compression of solid carbon (red circles). For a assumed step number and size, this models allow us to estimate how much plastic work occured during the ramp compression.

|

|

|

|

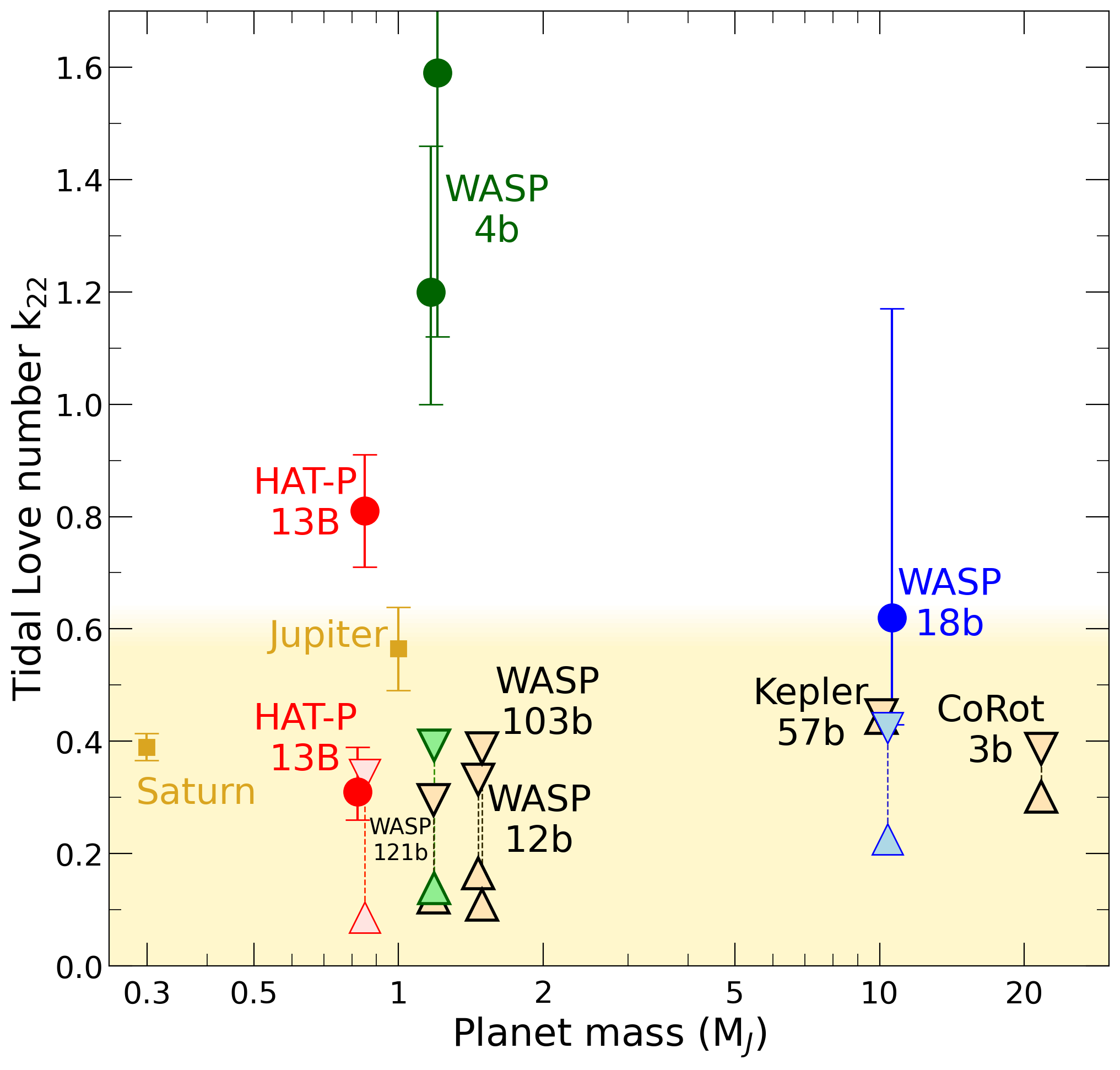

Tidal Love numbers from observations (solid cirlces) and our model predictions (open triangles) are compared for a series of exoplanets.

|

In our latest article, we study how the shape and gravity field of strongly irradiated, giant exoplanets is destorted by the external gravity field of their massive host stars. A planet's response to such external fields is expressed by the tidal Love number, k22, which has been inferred from telescope observations for the exoplanets WASP 4b (green color), HAT-P 13b (red), WASP 18b (blue). In the digram on the left, we compared these observations (solid circles) with our calculated values that we represent with triangles of corresponding colors. The upper triangles represent models without rocky core while the lower triangles show predictios for the largest possible cores. The beige symbols show our predictions for the exoplanets WASP 12b, 103b, 121b, Kepler 57b, and Corot 3b. We find that the static Love number, k22 cannot exceed the value 0.6 (yellow shaded region), which is in contradiction with some of the observations. We suggest additional observations to be made and existing data to be re-analyzed because this discrepancy may imply that the orbits of the observed exoplanets could be affected by other factors like not-yet-detected exoplanets. In our paper, we also derived the gravity harmonics, shape, of moment of inertia for our planet models.

|

|

|

|

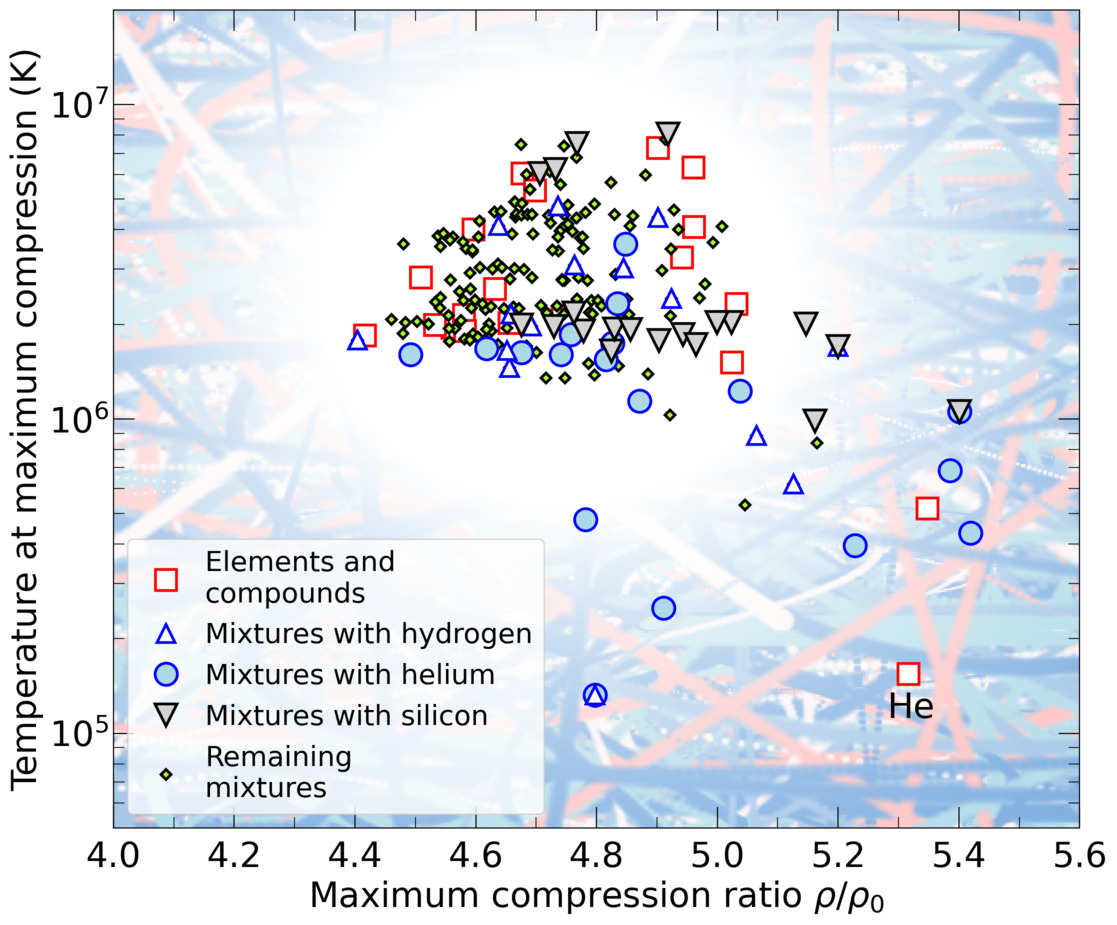

States of maximal shock compression of 200 compounds and mixtures predicted by our FPEOS database.

|

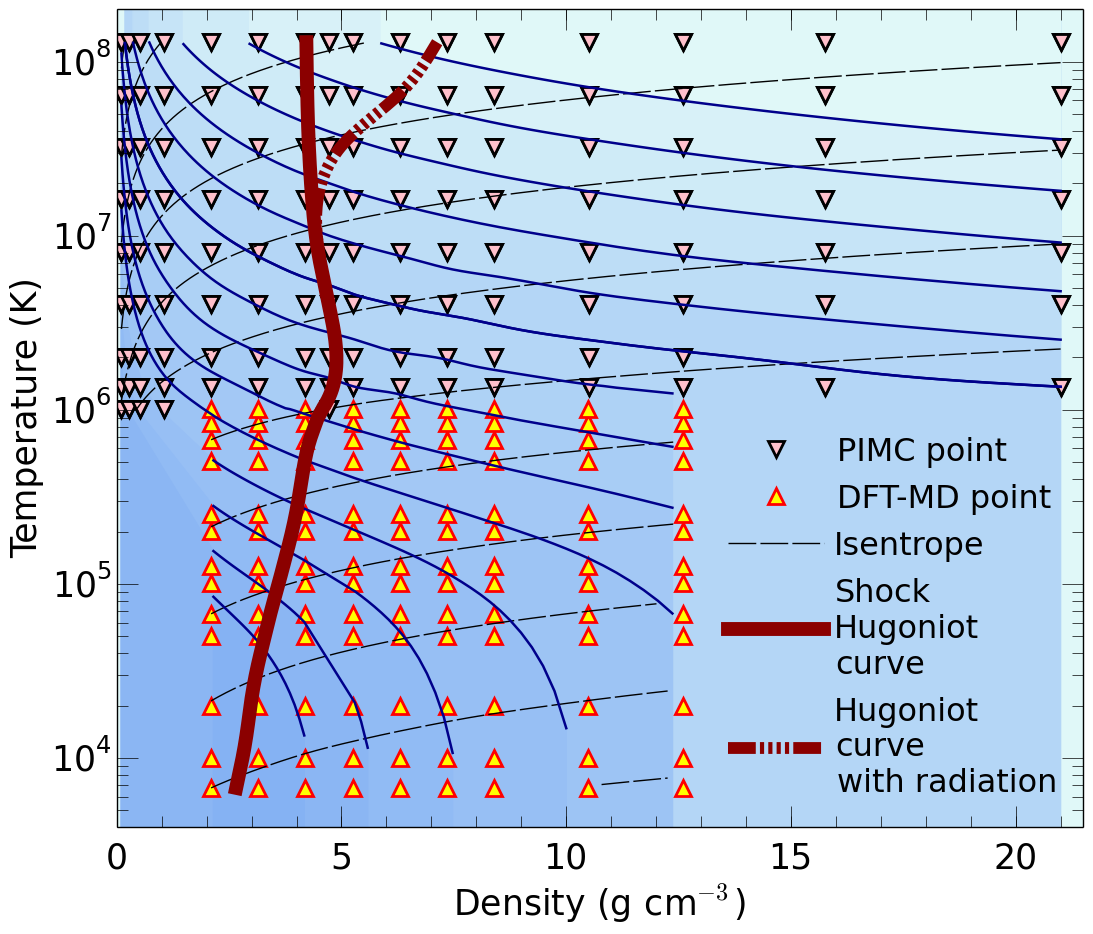

With the goal of making warm dense matter computations more reliable and efficient, we make available our first-principles equation of state (FPEOS) database for materials at extreme conditions. We provide our EOS tables the elements H, He, B, C, N, O, Ne, Na, Mg, Al, and Si as well as the compounds LiF, B4C, BN, CH4, CH2, C2H3, CH, C2H, MgO, and MgSiO3 that are solely based on results from ~5000 path integral Monte Carlo and density functional molecular dynamics simulations. For all these materials, we provide the pressure and internal energy over a density-temperature range from ~0.5 to 50 g/cc and from ~104 to 109 K. In our recent article, we compute isobars, adiabats, and shock Hugoniot curves in the regime of L and K shell ionization. Invoking the linear mixing approximation, we study the properties of mixtures at high density and temperature. We derive the Hugoniot curves for water and alumina as well as for carbon-oxygen, helium-neon, and CH-silicon mixtures. We predict the maximal shock compression ratios of H2O, H2O2, Al2O3, CO, and CO2 to be 4.61, 4.64, 4.64, 4.89, and 4.83, respectively. Finally we use the FPEOS database to determine the points of maximum shock compression for all available binary mixtures (left graph). We provide all FPEOS tables as well as C++ and Python computer codes for interpolation, Hugoniot calculations, and plots of various thermodynamic functions.

|

|

|

|

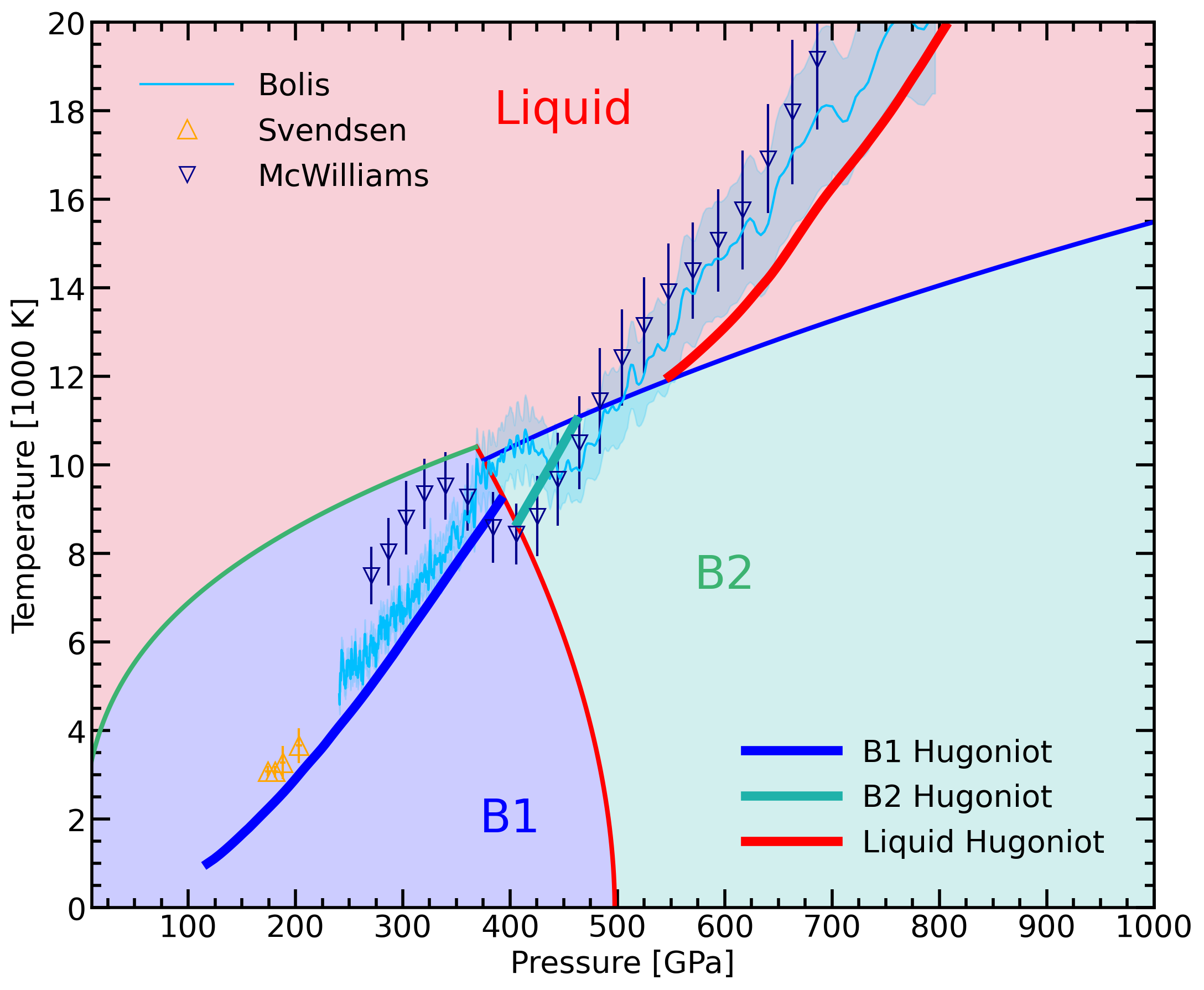

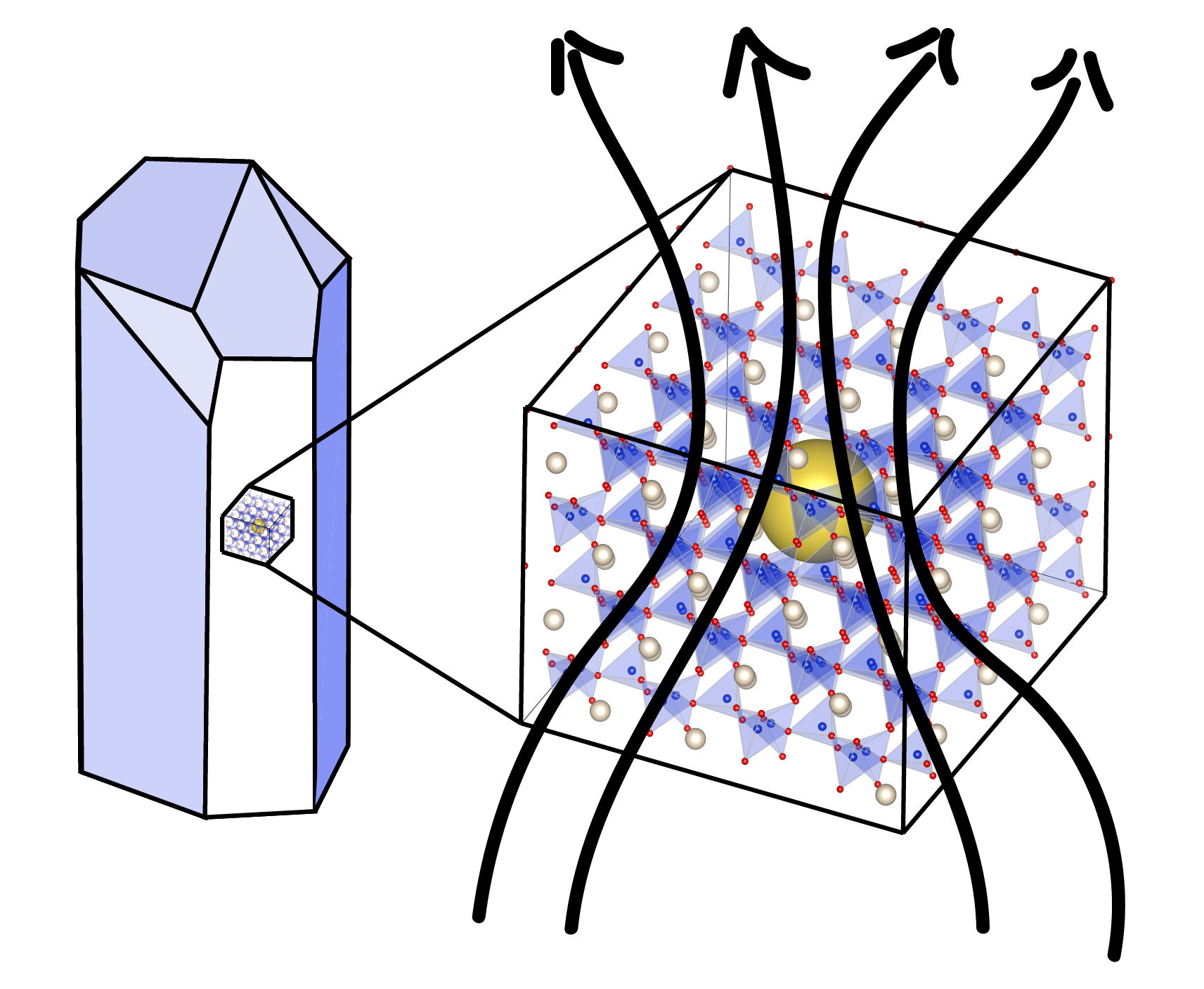

Phase diagram of MgO with liquid and solid B1 and B2 phases. Theoretical and experimental shock Hugoniots curves are compared.

|

With density functional molecular dynamics simulations, we computed the phase diagram of MgO in the pressure range from 50 to 2000 GPa up to temperature of 20000 K. Via thermodynamic integration (TDI), we derive the Gibbs free energies of the B1, B2, and liquid phases and determine their phase boundaries. The B1 structure is a NaCl-type crystal, in which Mg and O nuclei occupy alterating sites. Each atomic species by themselves forms a face-centered cubic lattice. In the B2 structure, is a CsCl-type crystal. Each atom species by themselves form a simple cubic structure. With our computer simulation, we show that anharmonic effects stabilize the B1 phase. We predict the B1-B2-liquid triple point to occur at approximately T = 10000 K and P = 370 GPa, which is higher in pressure than was inferred with quasi-harmonic methods. We predict the principal shock Hugoniot curve to enter the B2 phase stability domain but only over a very small pressure-temperature interval. This may render it difficult to observe this phase with shock experiments because of kinetic effects. Here are a copy of our article and a few slides in PPTX and PDF formats available to download.

|

|

|

|

Nanopore (yellow) in quartz crystal that may serve as a reservoir of helium atoms.

|

This joint theoretical-experimental project was sparked by a drastic disagreement between laboratory data and results from computer simulations for the diffusion of helium atoms in quartz crystals. This is important because the diffusion of noble gases in minerals is often utilized to reconstruct the thermal histories of rocks. Computer simulations of helium in perfect quartz crystals predicted that already at room temperature, all helium atoms would diffuse out of the crystal because the helium atoms encounter very lower energy barriers along the crystal's z channel. Taken at face value, this would imply all helium would have diffused out of the crystal before the experiments even began. Conversely, however, the lab measurements showed that temperatures between 70 and 220 oC were required for most helium atoms diffuse out of quartz crystals. In our article, this discrepancy is resolved by introducing the novel hypothesis that helium atom reside inside nanopores in the quartz crystal. The calculations showed that activation energy for helium atoms to diffuse from the nanopore into the crystal matched experimental data. A consistent effective diffusion model was constructed and the nanopore concentration was estimated to be approximately 10-5.

|

|

|

|

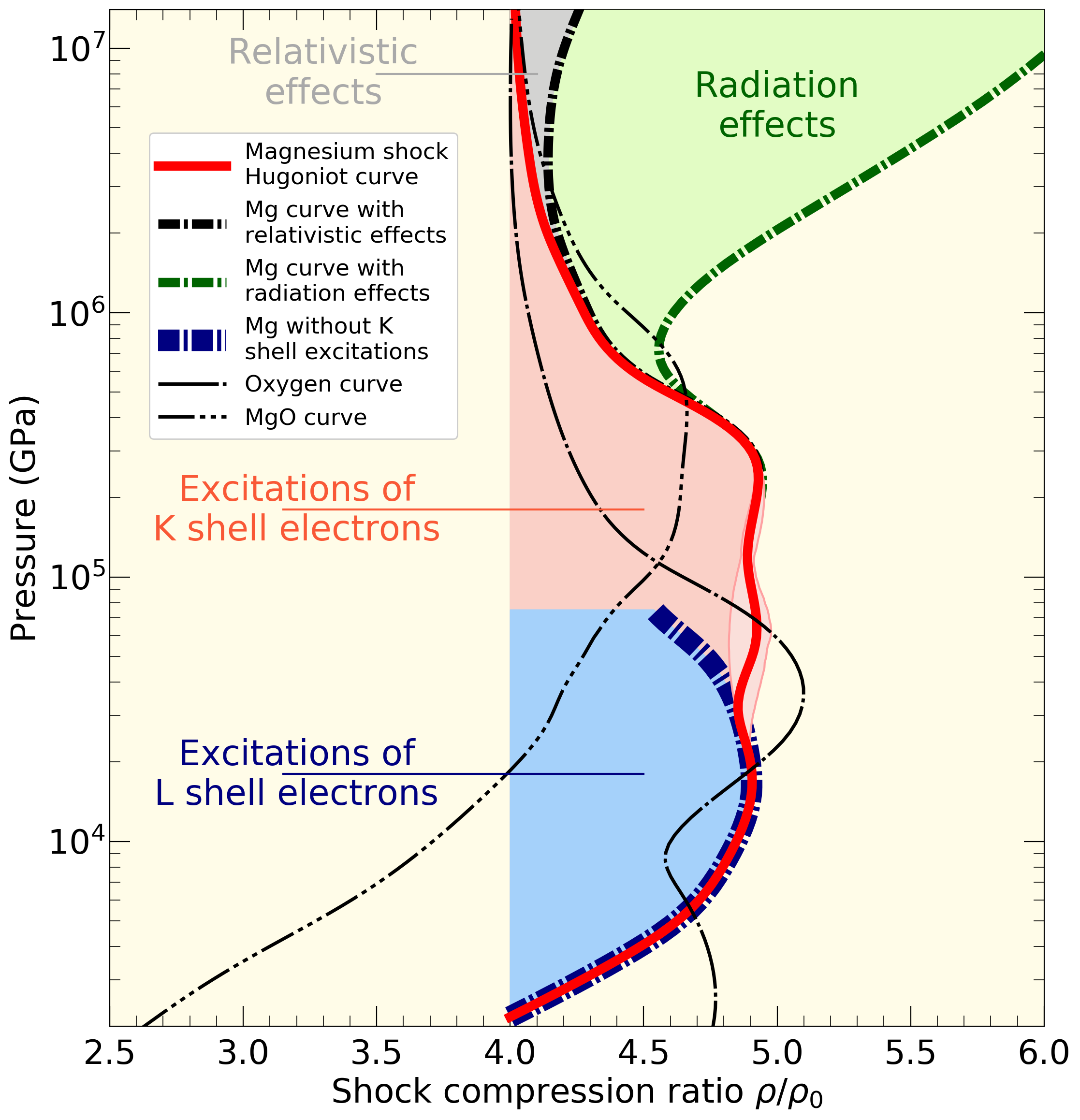

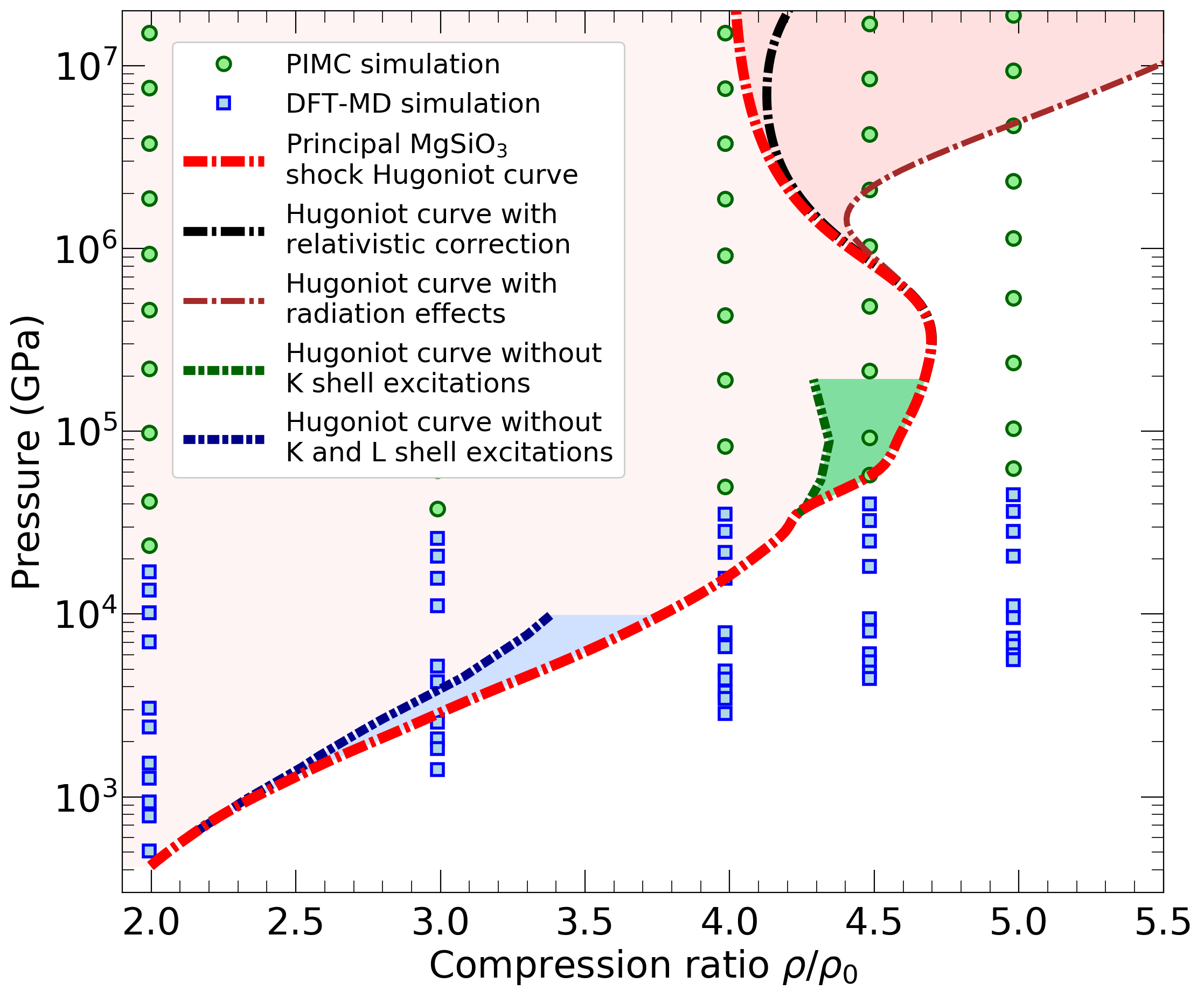

Four excitation mechanisms that control the shock Hugoniot curve of magnesium are plotted in pressure-density space.

|

In our latest article about warm dense matter, we employ path integral Monte Carlo and density function molecular dynamics simulations to study the properties of hot, dense magensium at high temperature and density. On the left, we show our prediction for the principal shock Hugoniot curve, which will most likely be the first quantity to be measure when laboratory experiments reach these conditions in the future. We identify four main excitation mechanisms that control the density that is reached in these compression experiments. In the low-pressure regime, excitations of L-shell electrons increase the shock compression ratio above the canonical value of 4. At higher pressure, the excitations of K-shell electrons maintain a high compression ratio of about 4.9. The compression ratio starts to decrease again once all K-shell electrons have been ionized. However, this decrease in compensated by the onset of radiative effects. Photons that are spontaneously emitted start making substantial controbutions to the energy and pressure. In compression, relativistic effects, that increase the energy of the electrons, play only a minor role.

|

|

|

|

Novel high-pressure structure of fluorine. Here are two alternate views A and B.

|

At the ambient conditions, fluorine is a highly reactive molecular gas. However, at high pressure, its properties change in a remarkable way. In our latest article, Mark Olson, Shefali Bhatia, Paul Larson and I use computer simulations to predict that fluorine forms a polyermic and metallic structure at 31 Mbar. Instead of the usual diatomic F2 bonding, the three quarters of the F atoms (blue) in the structure on the left are arranged in a 3D set of chains. The remaining quarter of atoms (red) occupied voids in between these chains. While flourine typically does not conduct electricity, our new high-pressure structure is an excellent conductor.

We obtained these results with a novel computer algorithm that allows us to efficiently predict crystal structures under symmetry and geometric constraints. We compare fluorine, chlorine and iodine and make reference to X-ray diffration experiments.

|

|

|

|

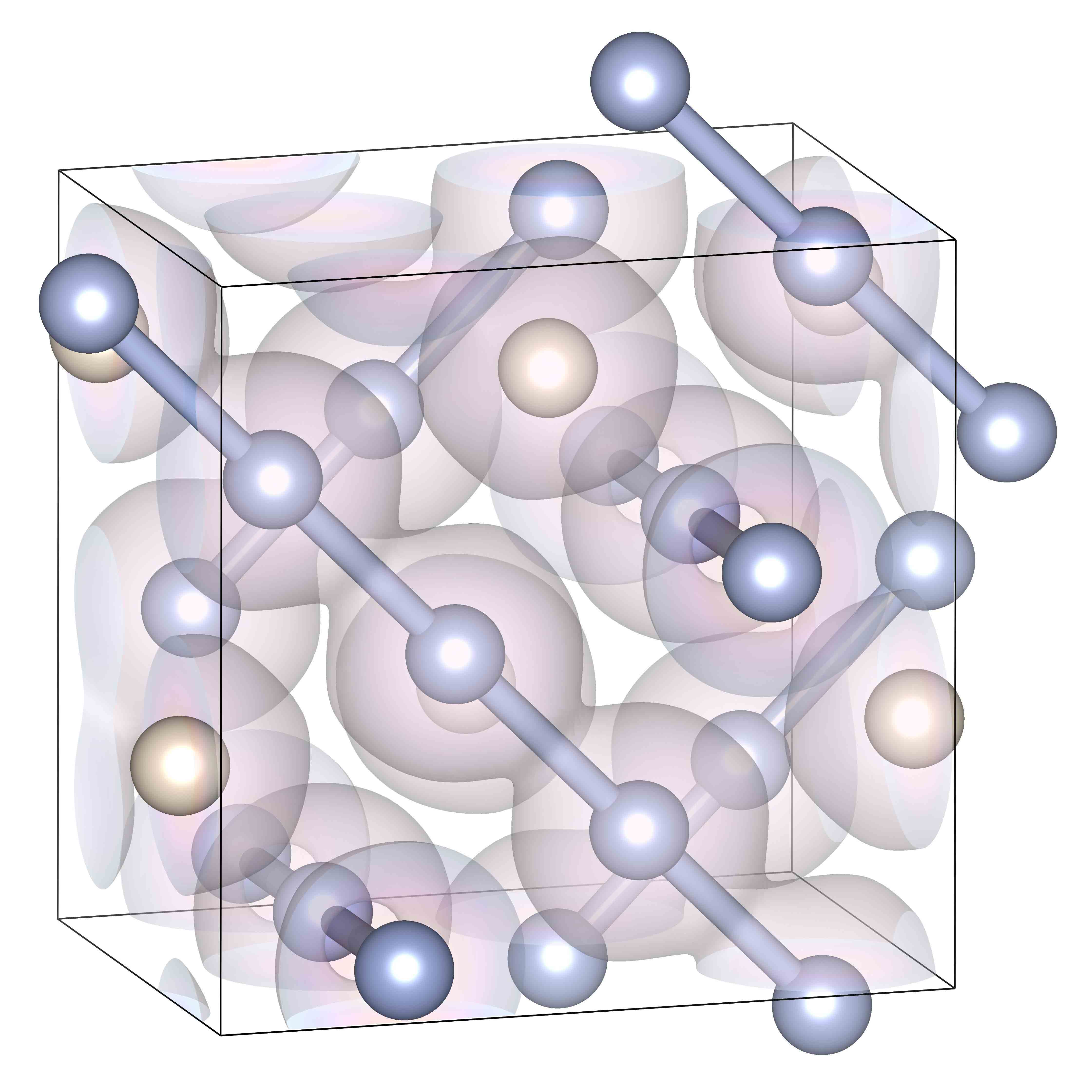

Signal to noise ratio for dectecting Jupiter's response to tidal forces from Io with the Juno spacecraft.

|

The four Galilean satellites, Io, Europa, Ganemede, and Callisto as

well as the sun all change the shape of Jupiter very slighly through

their gravitational forces. In this paper, we

calculate the strengh of this tidal response, which is represented as a series of Love numbers (knm).

We determine which Love numbers can be detected with the Juno spacecraft in the course of the on-going mission.

The graph on the left suggests that Io's k22, k33, k42, and k31 lead to

strong signals and should thus all be detectable. We predict a remarkably small range for Io's equilibrium Love

number k22 = 0.58976 ± 0.0001. Any deviation from this prediction can then be attributed with dynamic tidal effects.

|

|

|

|

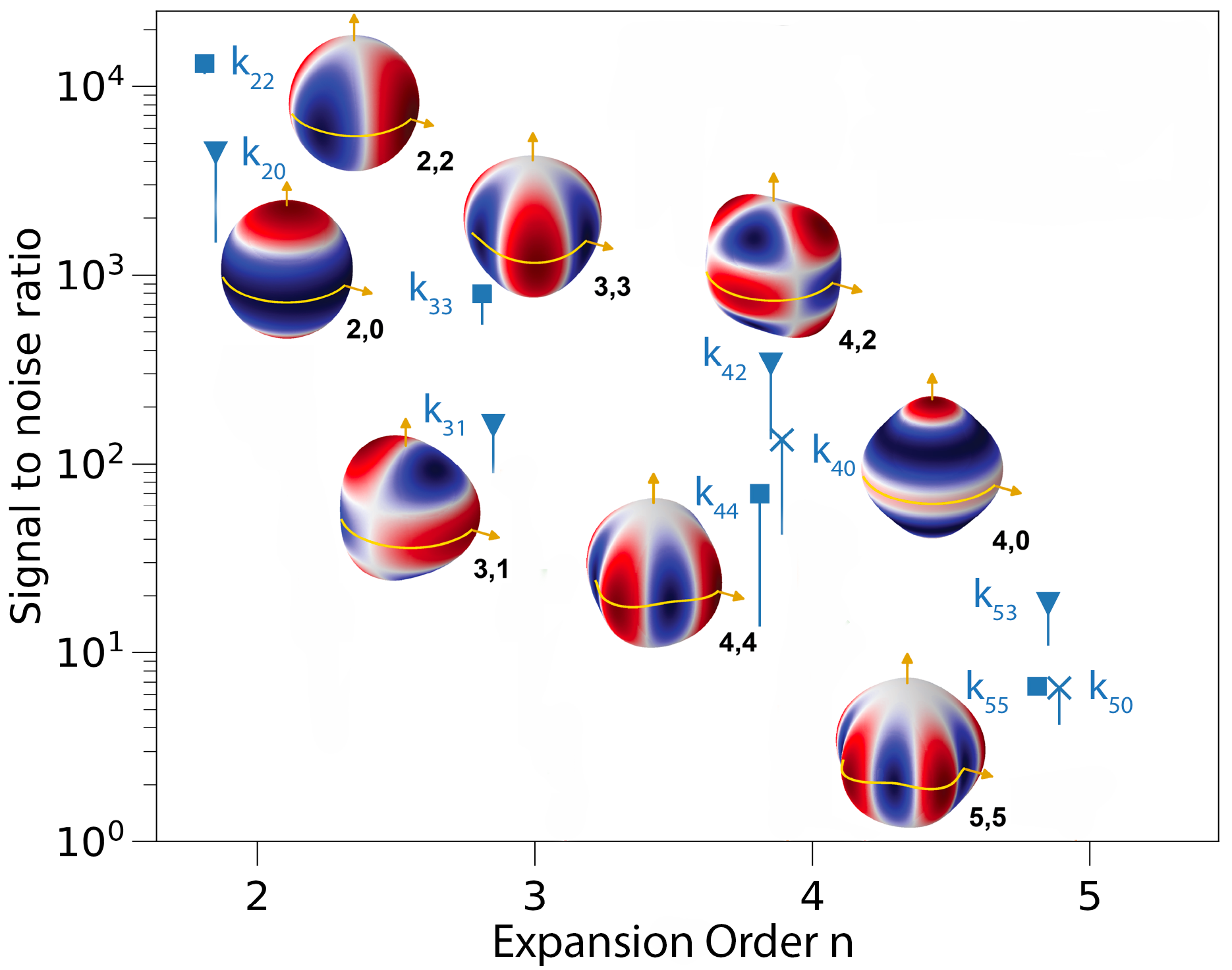

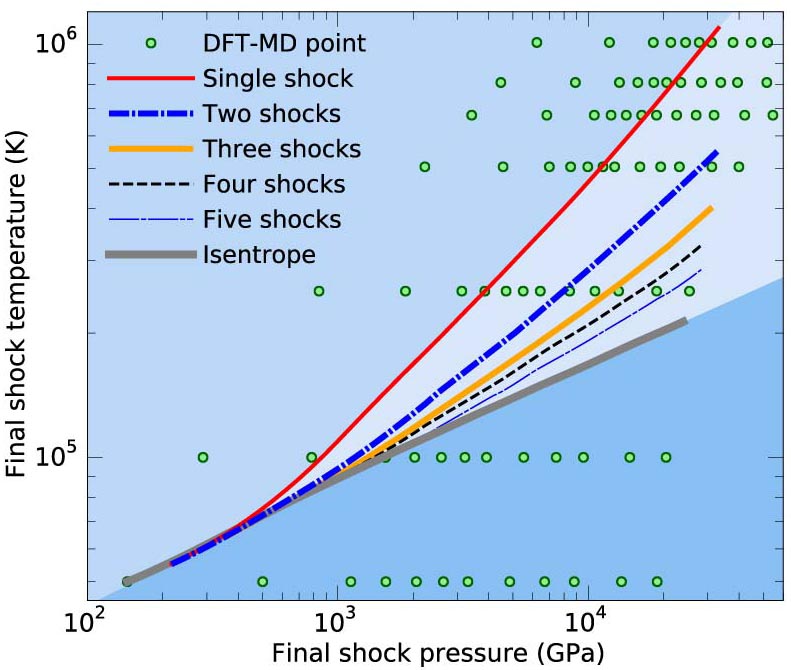

K shell (blue shade) and L (green shade) shell ionization effect on shock Hugoniot curve of MgSiO3.

|

Late during solar system formation, rocky planets

grow through massive impacts. The shock Hugoniot curve characterize

how hot and dense the rocky mantle becomes during an impact. In two

recent papers, we determined the shock Hugoniot curves of

MgO and

MgSiO3 with path

integral and density functional molecular dynamics simulations. In the

graph on the left, we show how the ionizations of K and L shell electrons

increases the density during an impact event. We also provided equation

of state tables over a large range of density-temperature conditions

for both materials.

|

|

|

|

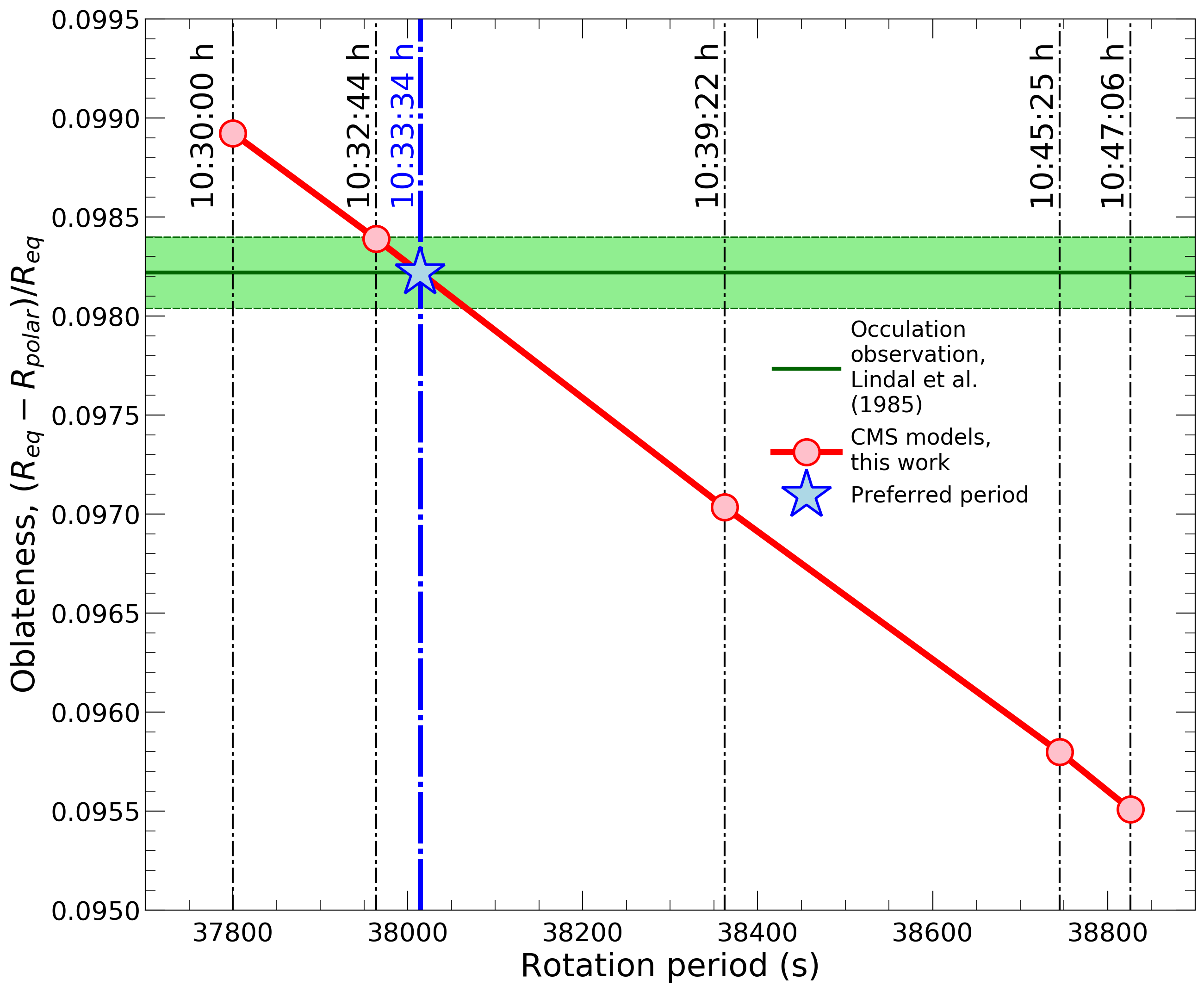

The graphs shows that only a rotation period of 10:33:34h ± 55s is compatible with the observed oblateness.

|

Saturn's rotation period cannot be measured directly

and has thus been very uncertain. Estimates vary between 10:32:45 h and

10:47:06 h, which is an uncomfortably large range that introduces

uncertainties into the analysis of various spacecraft measurements and

remote observations. The rotation period cannot be derived from

Saturn's magnetic field because it is perfectly aligned with the planet's

axis of rotation. This is not case for Jupiter and its rotation period

has been determined precisely to be 9:55:27 h. In our latest article, we combined

gravity data from the Cassini mission and Voyager's measurements of

the planet's shape to determine a rotation period of 10:33:34 h

± 55 s. The faster a planet rotates to more oblate it becomes,

which enabled us to infer its rotation period.

For this analysis,

we developed an accelerated version of the Concentric MacLaurin

Spheroid (CMS) method that enabled to constructed Monte Carlo

ensembles of plausible interior models. We currently apply this

approach to construct models for Jupiter's interior to match gravity

measurements by the Juno spacecraft. |

|

| |

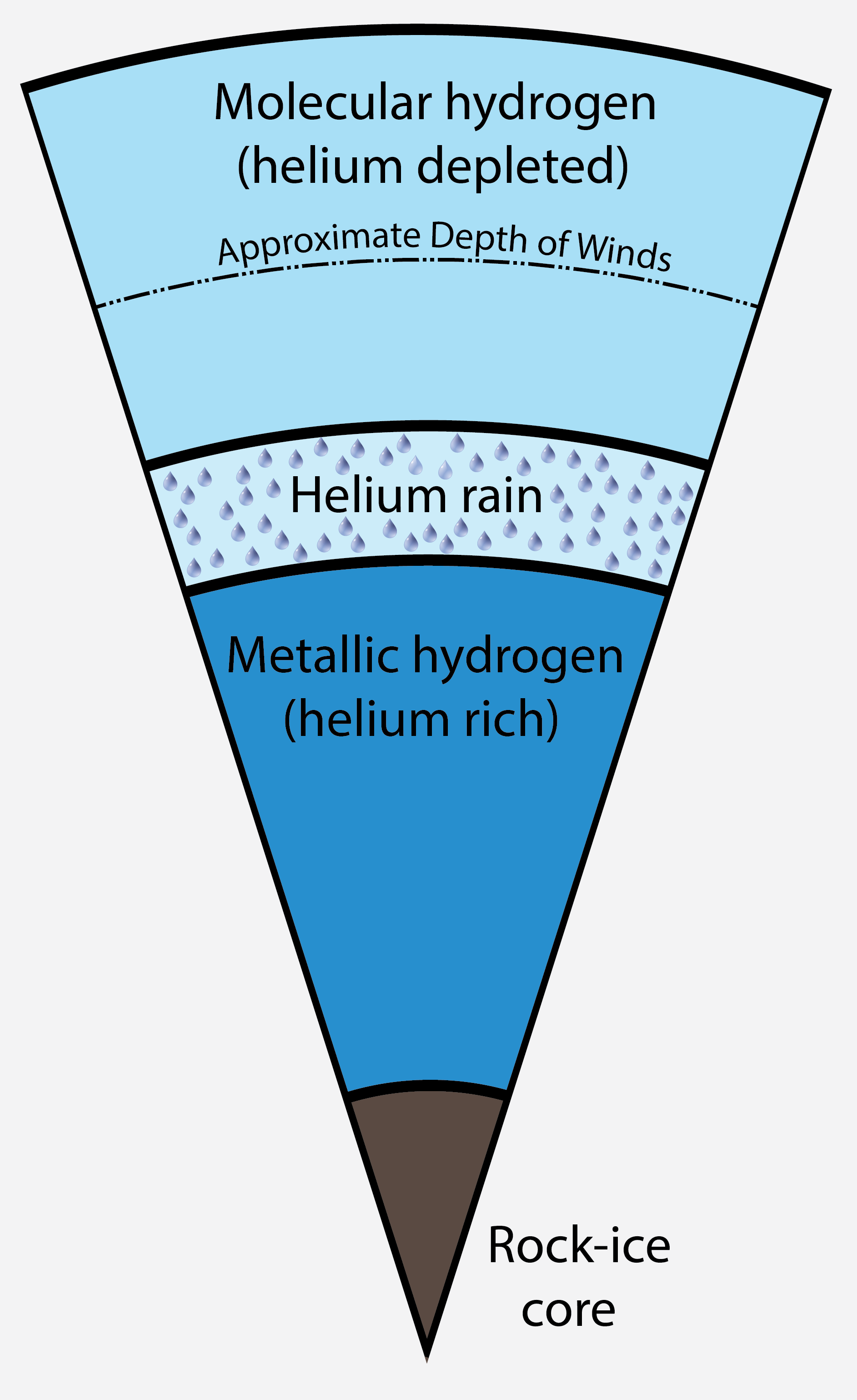

Planet Saturn was born naked but today it has rings and winds 9000 km deep.

|

Layers in Saturn's interior.

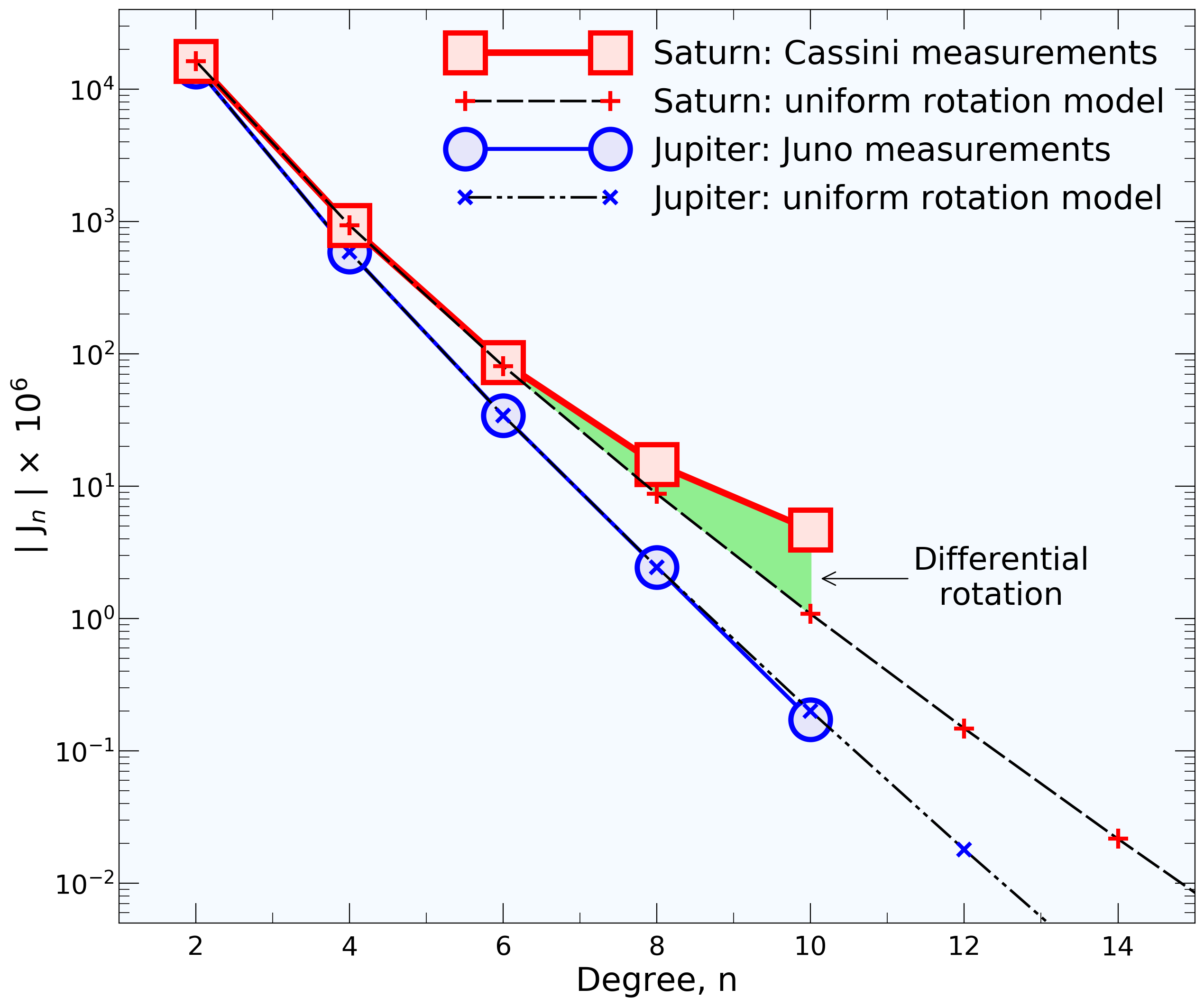

|

Gravity coefficients of Saturn and Jupiter.

|

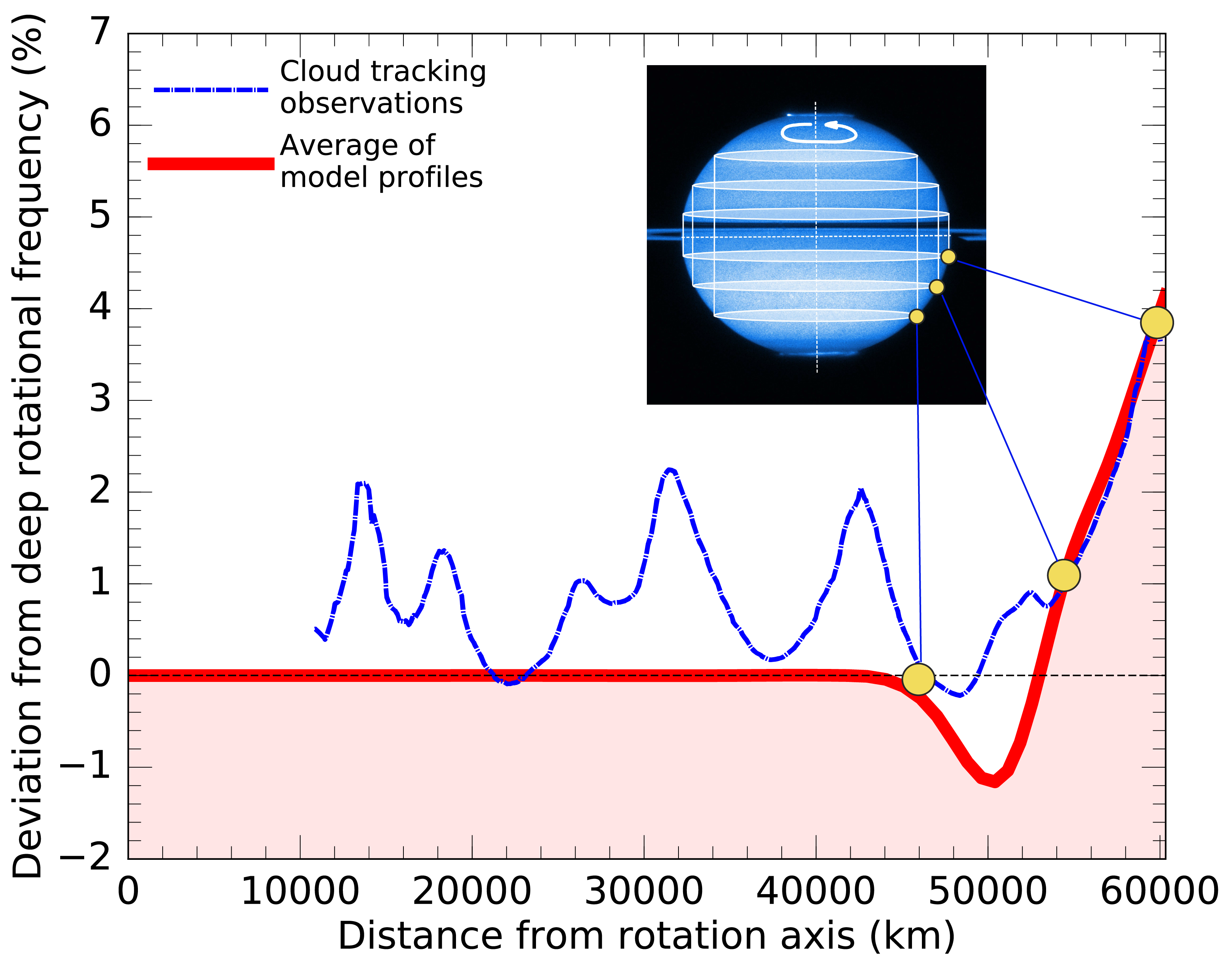

Varying rotation frequency in Saturn's interior.

|

This work is based on a collaborative article published in Science

that is entitled "Measurement and implications of Saturn's gravity

field and ring mass". For everyone to use, here are some slides in PPTX and PDF formats as well four graphics files that I prepared. Robert Sanders prepared this press release. Among the news coverage for this work, this Russian report stood out by explaining we had determined when Saturn became "The Lord of the Rings". Also here is an interview on NPR's radio show Science Friday about this work.

During its 13 years in orbit around Saturn, the Cassini

spacecraft has made a number of remarkable measurements of the planet

and its satellites. But only during its final 22 orbits it dove inside

its rings and measured the planet's gravity fields with unprecedented

precision. Two important findings emerged:

The winds in Saturn's atmosphere are massive and at least 9000 km deep:

We had prepared a suite of

models for Saturn's interior that included different core masses

and amounts of helium

rain. We calculated the expected gravity field and were pretty sure

Saturn's gravity coefficent J8 would fall between -9 and -8

x 10-6. We were completely surprised when the Cassini

spacecraft measured J8 to be -14 x 10-6, which

implied something important was missing from all models that we had

constructed. After we added deep and massive winds to our interior

models we were able to match all gravity coefficients. The winds need

to be at least 9000 km deep. The winds in Saturn atmosphere had been

observed before but no one had assumed they would reach that deep. The

first evidence of very deep winds in giant planets only came late last

year when measurements of the Juno spacecraft predicted the winds on

Jupiter to be between 3000 and 5000 km deep.

Saturn's rings are young and only formed 10-100 million years

ago: When I admired Saturn's spectacular rings, I naively assumed

they were as old as the planet itself (4.5 billion years). The first

gravity measurement of the ring mass now tells us otherwise. They

contain only about 0.4 Mimas masses (2000 Mimas masses = 1 Earth moon)

worth of material, which points to a surprisingly young ring age of only

between 10 and 100 million years. Before that Saturn presumably did

not have any rings. (On our slides,

we explain how one relates ring mass and age.) This tells us a

dramatic event must have occurred near Saturn in our recent solar system

history. 100 million years ago, the dinosaurs still roamed on

Earth. They disappeared when a giant impact occured near the

Yucatan peninsula 65 million years ago. Now we have evidence that a

drastic event occurred near the Saturnian system that produced a gazillion

pieces of icy rubble that make up the rings today. This suggests that our solar system is not such a

stable and happy place as one might think. We assume the rings are

either the leftover debris from a comet that was tidally disrupted by

Saturn's extreme gravity just like the Shoemaker-Levy

comet was pulled apart by Jupiter. Alternatively Saturn originally

had multiple satellites, their orbits become unstable, and it came to a

gigantic collision. We cannot tell which scenario is more likely but we

do know something drastic must have happened in the Saturnian system

fairly recently by astronomical standards.

|

|

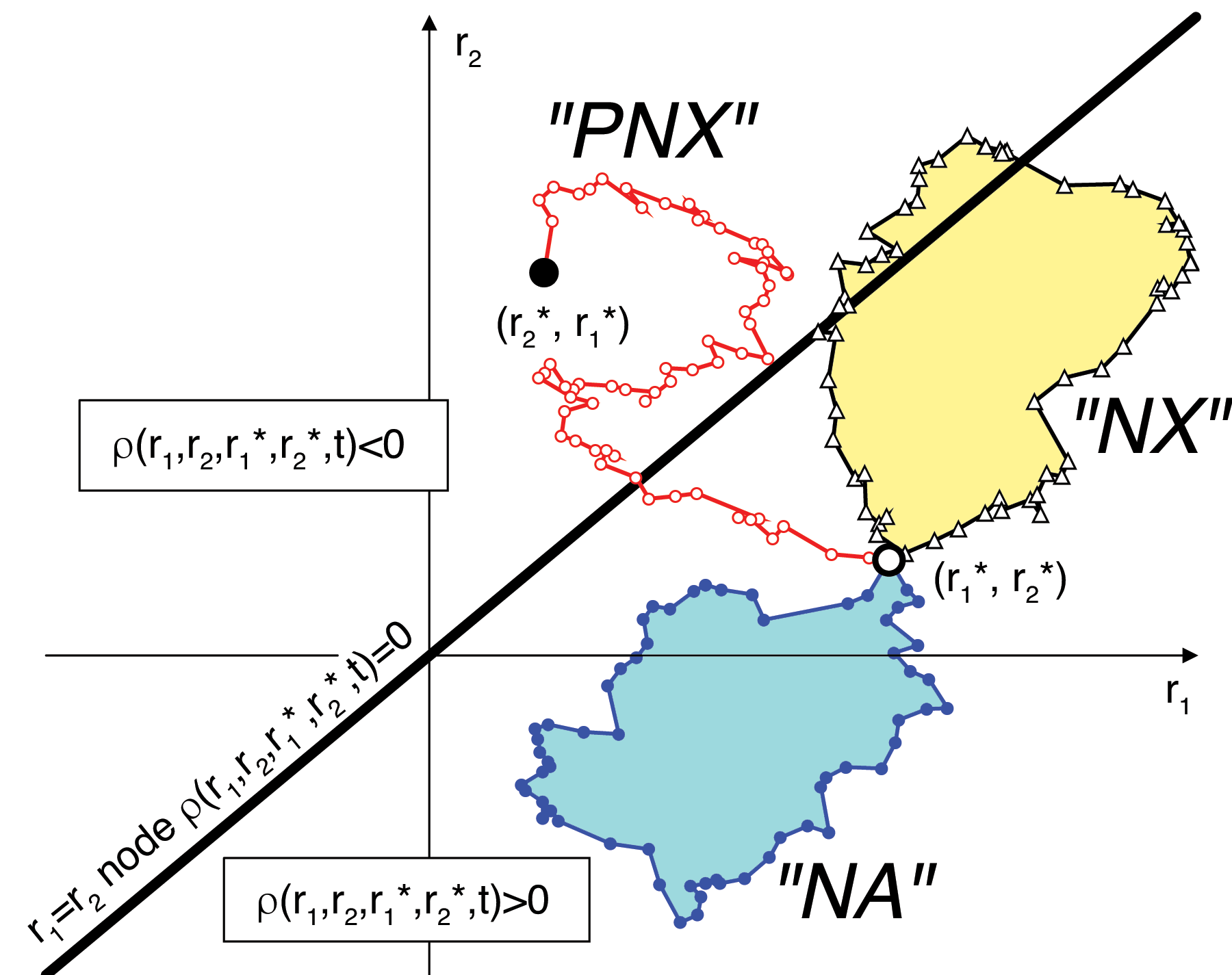

Different paths that enter into PIMC simulations of just two particles. Node-avoiding (NA), node-crossing (NX) as well as permuting, node-crossing (PNX) paths are illustrated. The diagonal black line denotes the node the density matrix, ρ=0.

|

Modeling the behavior of interacting quantum systems on a classical computer is challenging. Here we the Feynman's path integral method to map a system of quantum particles onto a system of classical paths. While most thermodynamic properties can be derived from simulations of closed paths, the computation of the momentum distribution requires open paths. In this article, we compute the momentum distribution of the homogeneous electron gas with path integral Monte Carlo (PIMC) simulations.

Since thsi is a fermionic system, we employed the restricted path approach to deal with the fermion sign problem.

In the restricted PIMC method, only node-avoiding (NA) paths contribute. For two particles, the nodal restriction prohibits all permutations. However, if simulations with the direct fermion method are performed no restrictions are applied. Nonpermuting paths that cross the nodes (NX) and those that avoid it (NA) both enter with a positive sign. Permuting paths (PNX) are now permitted and enter with a negative weight given by the (-1)P factor.

|

|

| |

|

|

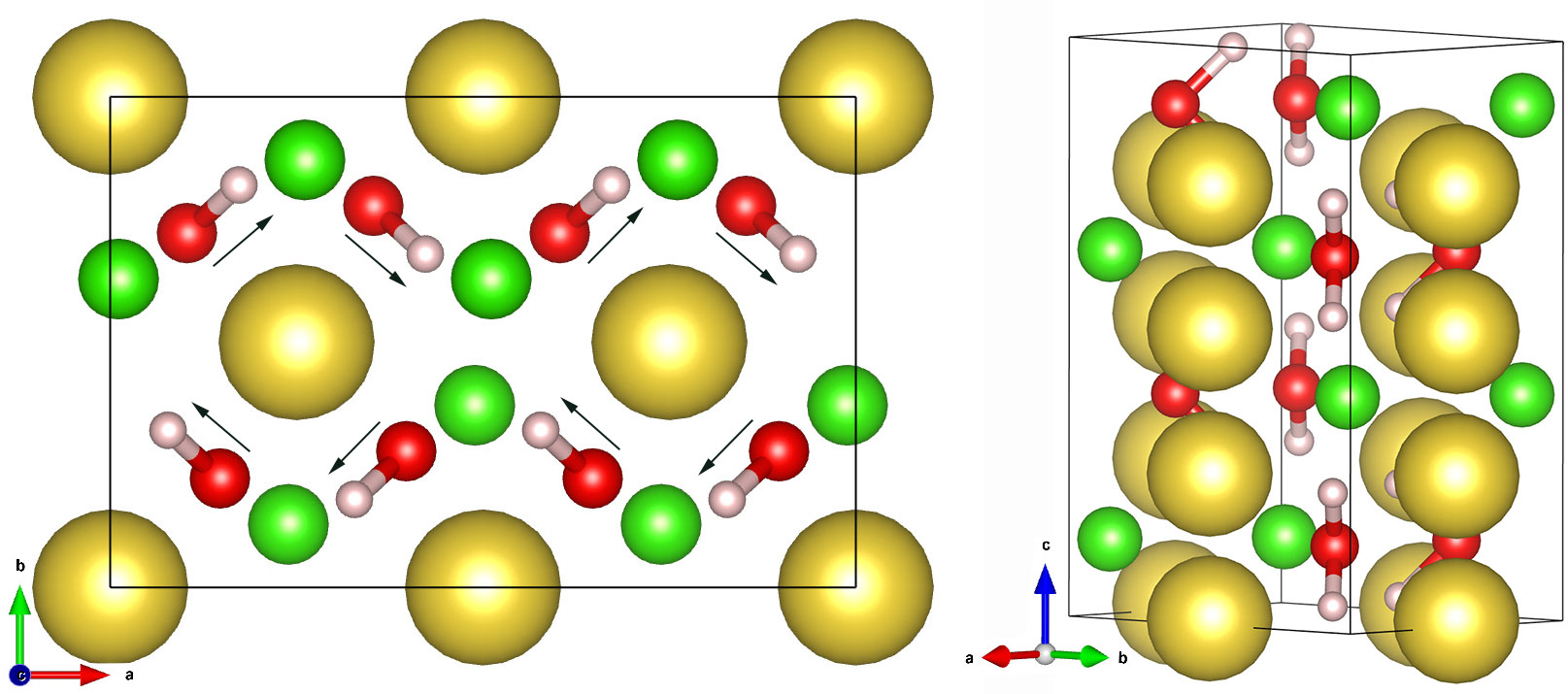

Crystal structure of our new water-salt compound that we predict to form at high pressure. The yellow, green, red, and light spheres denote the positions of the chlorine, sodium, oxygen, and hydrogen atoms. The small arrows denote the dipole of the water molecules that cancel each other out.

|

We developed a new symmetry-driven structure search (SYDSS) algorithm

to predict novel materials with ab initio simulations. In our

recent article, we predict water and

salt form a novel compound at high pressure. While at ambient

conditions, water can only incorporate a modest amount of salt, we

predict that both materials form a novel 1:1 stoichiometric

H2O-NaCl compound at high pressure. It is well-known that

high pressure changes the crystal structure of materials, novel

materials may form, and immiscible compounds can become miscible. In

the same article, we also predict two

unusual carbon oxides, C2O and C4O, to form while

at ambient pressures, only CO2 and CO are known to exist.

| |

|

Solid silicates (blue line) are semi-conductors that have excitation gap (green region). Liquid silicates (red line) have no gap and are thus semi-metals. They conduct electricity reasonably well.

|

With the Kepler satellite, thousands of new exoplanets were

discovered. Many of them have been described as Super-Earths since

they are larger than Earth but also have a rocky composition. Their

interiors are much hotter than Earth's and part of their mantles

are likely to be liquid. In our recent article, we

showed that the electrical conductvity of liquid mantles are

sufficiently high so that Super-Earths can generate magnetic fields

with their mantles. This is a new regime for the generation of

planetary magnetic fields. Our magnetic field on Earth is generated in

the liquid outer iron core. On Jupiter, it arises from the convection

of liquid metallic hydrogen. On Uranus and Neptune, it is assumed to

be generated in the ice layers. Now we have added molten rocks to

this diverse list of field generating materials. This also implies

that the magma ocean that existed on the early Earth generated a

magnetic field.

| |

|

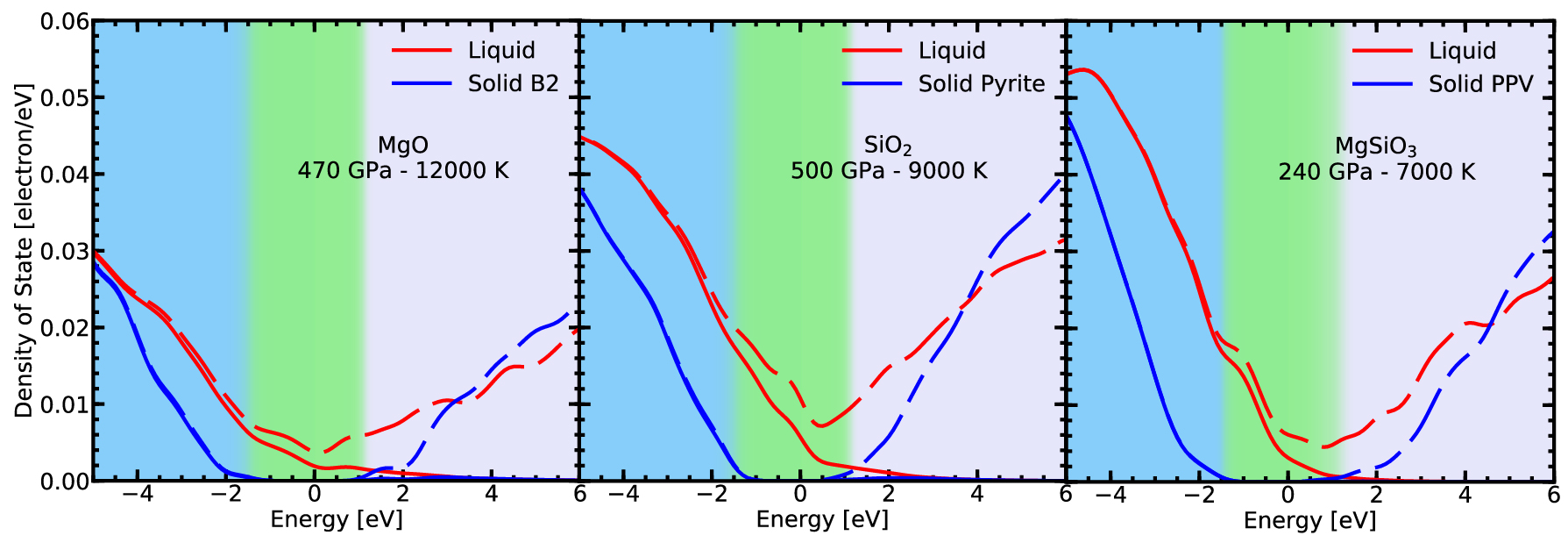

T-P path of experiments with multiple intermediate shocks.

|

Valence band gap predicted with our DFT-MD simulations and

two semi-analytical models.

|

In our recent article, we studied

aluminum at extreme pressure and temperature conditions with path

integral Monte Carlo and density functional molecular dynamics

simulations. We derive the equation of state and various electronic

properties. In laboratory experiments, one typically uses shock waves

to reach such extreme conditions. The material becomes very hot if just

a single shock is employed. The graph on the left illustrates that

comparatively low, nearly isentropic temperature conditions can be

reached when a number of smaller

shocks are employed instead.

Aluminum is metal. However, there is gap in the electronic density of states between the 2p and the

conduction band. This gap is expected to close at very high density when

the bound 2p state merge with the free particle states. The two

semi-analytical theories (Stewart-Pyatt and REODP) predict the gap to

close rather rapidly with increasing compression. Conversely, with my

DFT-MD simulations, we find the magnitude of the gap hardly changes

up to 12-fold compression. This stark disagreement is subject to

further investigations.

| |

|

Superionic water in novel P21/c structure.

|

Superionic H2O2 compound.

|

Deep in the interior of Uranus and Neptune, water has been predicted

to occur in a novel, superionic

form. In our latest article, we use

ab initio Gibbs free energy calculations to demonstrate that

superionic water changes from face-centered

cubic form to a novel structure with P21/c symmetry

at 23 Mbar. At even higher pressure of 69 Mbar, superionic water is no

longer stable. It decomposes into two superionic

H2O2 and H9O4 compounds.

|

|

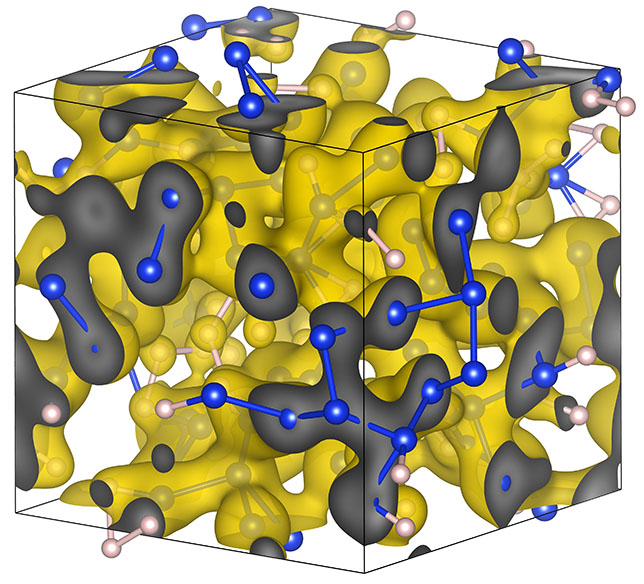

Polymeric CH structure at high pressure and temperature. The blue and white spheres denote the C and H atoms, respectively. The yellow isosurface denotes the electron density.

Polymeric CH structure at high pressure and temperature. The blue and white spheres denote the C and H atoms, respectively. The yellow isosurface denotes the electron density.

|

|  Density-temperature conditions of our simulations. The black and red triangles label our PIMC and DFT-MD simulations, respectively.

Density-temperature conditions of our simulations. The black and red triangles label our PIMC and DFT-MD simulations, respectively.

|

|

In these two articles, (a)

and (b), we investigate CH

pastic materials at extreme pressure-temperature conditions that are

relevant to inertial confinement fusion experiments. Such hydrocarbon

plasmas are of broad interest to laser shock experimentalists, high

energy density physicists, and astrophysicists. Our project has been

support by a Bluewaters computer

time allocation.

|

|

|

|

Jupiter interior model with a dilute core.

|

Most models for Jupiter's formation assume it started with a dense

core of rock and ice. Once that reached a critical mass of ~10 Earth

masses, the run-away accretion of hydrogen-helium gas set in, which

lasted until Jupiter had consumed all the gas in its vicinity,

leading to a giant planet of 318 Earth masses.

While the temperature and pressure conditions in the planet's center

reached ~16000 K and ~40 Mbar, the fate of the core remains

ill-understood. Typical core materials like water ice, MgO, SiO2, and iron are all

soluable in hydrogen, which assumes a metallic state under these

extreme conditions. It is not unclear, however, if there was

sufficent convective energy in Jupiter's early history to spread out

the heavy core materials against the forces of gravity.

Here we construct a series of models for Jupiter's interior in

order to match the recent gravity measurments of the Juno

spacecraft. We demonstrate models with a dilute core match the

observations better lending support to the hypothesis that heavy

material in Jupiter's core have been redistributed over a

substantial fraction of the planet's radius. Different terms ranging

diffuse, dilute, expanded and even fuzzy have been invoked to

describe such a core. A Jupiter model with a dilute core is shown on the left.

|

|

|

|

Calcite I crystal structure. The blue, brown, and red spheres denote the Ca, C and O ions respectively. The red isosurface denotes the electron density.

Calcite I crystal structure. The blue, brown, and red spheres denote the Ca, C and O ions respectively. The red isosurface denotes the electron density.

|

|  Calcite V propeller phase. The yellow isosurface denotes the density of oxygen ions that emerges from the propeller rotation of the carbonate CO32- ions.

Calcite V propeller phase. The yellow isosurface denotes the density of oxygen ions that emerges from the propeller rotation of the carbonate CO32- ions.

|

With ab initio computer simulations, we studied the unusual

propeller motion of the carbonate CO32- ions in

phase V of calcite (CaCO3). We found that the ions

perform a tumbling motion and instead of rotating like a perfectly

mounted propeller. We also demonstrated that this phase is denser than

the liquid implying a negative slope of the melting line.

|

|

|

|

Computer simulation of a hot, dense mixture of hydrogen (white), helium (green) and iron (yellow spheres) atoms.

Computer simulation of a hot, dense mixture of hydrogen (white), helium (green) and iron (yellow spheres) atoms.

|

Giant planets are primarily composed of hydrogen and helium but they

also contain a small amount of heavier elements. In the atmosphere

they make up less than 3% by mass but they dominate the planets

opacity. Without their presence we would be able to see through

Jupiter's molecular layer and directly observe the planet's metallic

interior where its magnetic field is generated. Most scientists

assume Jupiter has a core composed of heavy elements. Its size and

composition is uncertain but we estimated its mass to be worth 12

Earth

masses. The

total heavy element fraction in the planet could be as high as

7%.

In

this article, Francois Soubiran investigates the properties of

various heavy elements in giant planet interiors. The equation of

state is computed for C, N, O, Si, Fe, MgO and SiO2 mixed

with hydrogen and helium. Effective mixing rules are derived to make

models of giant planet interiors more accurate.

|

|

|

|

|

This article provides an overview of how models of giant planet

interiors are constructed. We review measurements from past space

missions that provide constraints for the interior structure of

Jupiter. We discuss typical three-layer interior models that consist

of a dense central core and an inner metallic and an outer molecular

hydrogen-helium layer. These models rely heavily on experiments,

analytical theory, and first-principle computer simulations of

hydrogen and helium to understand their behavior up to the extreme

pressures ~10 Mbar and temperatures ~10,000 K. We

review the various equations of state used in Jupiter models and

compare them with shock wave experiments. We discuss the possibility

of helium rain, core erosion and double diffusive convection may

have important consequences for the structure and evolution of giant

planets.

The diagram on the left shows the radius and fractional mass as function of mass for a typical model. The color label various layers.

|

|

|

|

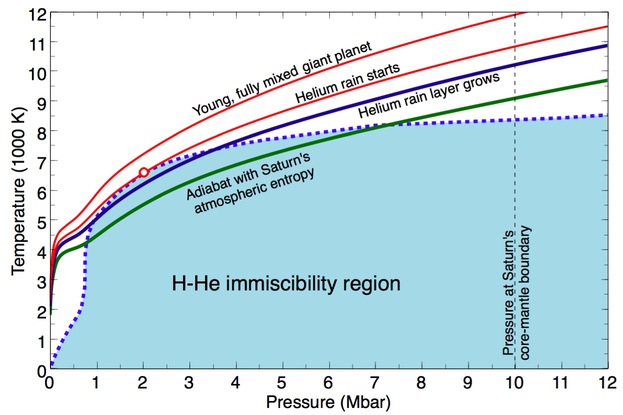

Temperature-pressure profiles for Jupiter's interior during the planet's evolution.

Temperature-pressure profiles for Jupiter's interior during the planet's evolution.

|

When the Juno

spacecraft arrives at Jupiter in July of this year, it will map

out the planet's gravity field with unprecedented precision. What can

we expect to learn about Jupiter's interior? Based on earlier

measurements and on results from ab initio computer simulations

of mixtures of hydrogen, helium, and some heavier elements, Bill Hubbard

and I put together a number of different interior models (ApJ, 2016)

. We predict a massive core of 12 Earth masses consistent with earlier models. Furthermore, we

predict that helium rain

has occurred on this planet for some time, which is a direct

consequence of combining the measurements of the Galileo

entry probe with results from ab initio calculations for

the hydrogen-helium immiscibility

and adiabats.

|

|

|

|

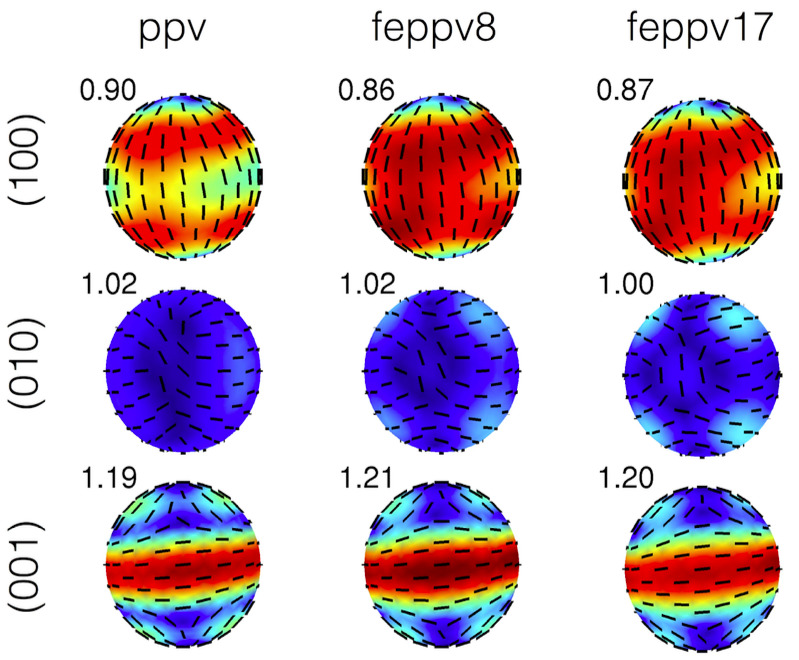

Shear wave splitting strength.

|

Despite a wealth of seismic observations, many questions about the

compositions of the Earth's mantle have remained unanswered. In a

recent study (EPSL, 2016) lead by Shuai Zhang, we show that

the assumption of a pyrolitic composition for the deep Earth is in

good agreement with the preliminary reference Earth model (PREM), which is

a 1D seismological representation of the Earth's interior. In collaboration with

Tao Liu and Stephen Stackhouse (Leeds U.) and Sanne Cottaar (Cambridge

U.), we performed ab initio molecular dynamics to calculate the

elastic and seismic properties of pure, Fe3+ and

Fe2+, and Al3+ bearing MgSiO3

perovskite and post-perovskite over a wide range of pressures,

temperatures, and Fe/Al compositions.

|

|

|

|

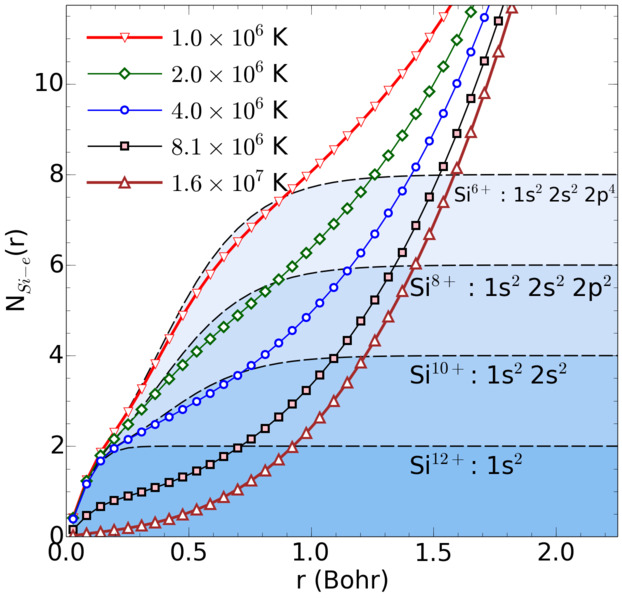

Nucleus-electron correlation functions.

Nucleus-electron correlation functions.

|

In our recent publication in Physical

Review Letters, Kevin Driver and I extended the applicability range of

fermionic path integral Monte Carlo simulations to heavier elements

and lower temperatures by introducing various localized nodal

surfaces. Hartree-Fock nodes yield the most accurate prediction

for pressure and internal energy that we combine with the results from

density functional molecular dynamics simulations to obtain a

consistent equation of state for hot, dense silicon under plasma

conditions and in the regime of warm dense matter (2.3-18.6 g/cc,

5x105 - 1.3x108K). The shock Hugoniot curve is

derived and the structure of the fluid is characterized with pair

correlation functions. On the left, we estimate the degree of

ionization by comparing the integrated nucleus-electron pair

correlation functions from PIMC (symbols) with results for isolated

atoms (black dashed lines).

|

|

|

|

Phase diagram of nitrogen.

|

In two articles, Kevin Driver, Francois Soubiran, Shuai Zhang, and I

combine path integral Monte Carlo simulations and density functional

molecular dynamics to study oxygen

and nitrogen

in the regime of warm dense matter. We characterize both material at

extreme pressure and temperature conditions that exist in stellar

interiors and can be probed with shock wave experiments. We use pair

correlation functions and the electronic density of states to describe

changes in the structure of the plasma. We compute the shock Hugoniot

curves to compare with laboratory experiments. For nitrogen, we

characterize the regime of molecular dissociation that leads to a

region of dP/dT<0 at high pressure, which is shown in green in the

phase diagram on the left.

|

|

|

|

Simulation of a H2-H2O mixture.

Simulation of a H2-H2O mixture.

|

Ice giant planets are typically assumed to have a hydrogen-rich

atmosphere, an intermediate ice layer, and a rocky core. Such

three-layer models satisfy the observational constraints for Uranus

and Neptune. However, it remains unclear whether these planets have

oceans, which would imply the existence of a sharp boundary

between the hydrogen and water layers. Alternatively, the density and

the water contents of the atmosphere could increase gradually. Recent

laboratory experiments by Bali at el. (2013) favored the ocean

hypothesis. In our ApJ

article, Francois Soubiran and I used ab initio computer

simulations to determine whether H2 and H2O are

missible at high pressure. Contrary to the experimental predictions,

we find that both materials are fully miscible under ice giant

interior conditions. We predict that these planets can only have

oceans if icy building blocks were delivered before the gas was

accreted during planet formation.

|

|

|

|

Simulation of a liquid iron-MgO mixture. The brown,

green, and red spheres denote Fe, Mg, and O atoms. The grey surfaces

show the electron density.

Simulation of a liquid iron-MgO mixture. The brown,

green, and red spheres denote Fe, Mg, and O atoms. The grey surfaces

show the electron density.

|

All known terrestrial planets have a separate iron core and a rocky

mantle because metallic iron has a low solubility in rocky materials

under typical pressure-temperature conditions in the planetary

interiors. However, at sufficiently high temperatures, all materials

eventually become miscible, even oil and water.

In our recent article,

Sean Wahl and I use ab initio computer simulations to

determine what temperature would be required for iron and MgO to

become miscible in all proportions. We find that the required

temperature rises from 4000 to 10,000 K as the pressure is increased

from 0 to 500 GPa. Such extreme conditions can be reached during a

giant impact on a terrestral planet, implying that not all iron would

settle into core during such an event.

|

|

|

|

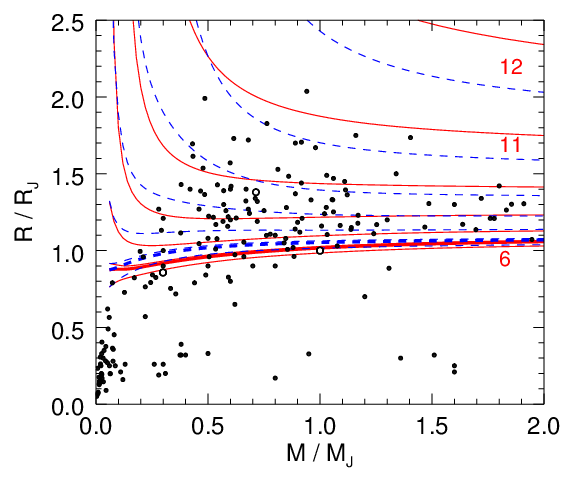

Revised mass-radius relation

Revised mass-radius relation

for giant exoplanets. Our new simulation data are shown in red.

|

Using density functional molecular dynamics simulations, we determine

the equation of state for hydrogen-helium mixtures spanning

density-temperature conditions typical of giant planet interiors. In

our manuscript, a comprehensive equation

of state table with 391 density-temperature points is

constructed and the results are presented in form of two-dimensional

free energy fit for interpolation.

We present a revision to the

mass-radius relationship which makes the hottest exoplanets increase

in radius by ~0.2 Jupiter radii at fixed entropy and for masses

greater than ~0.5 Jupiter mass. This change is large enough to

have possible implications for some discrepant "inflated giant

exoplanets".

Our full EOS table as well as our free energy interpolation code has just been made available here.

|

|

|

|

|

In the interiors of Uranus and Neptune (dashed lines in the left

figure), water is predicted to occur in a superionic state where the

oxgyen atoms remain stationary like in a solid while the hydrogen

atoms diffuse throughout the crystal like a fluid. Here, we

show that, at 1.0±0.5 Mbar, the oxygen sub-lattice in superionic

water changes from a body-centered cubic lattice (middle) to an

face-cented cubic lattice (right). This transformation lead to a more

efficient packing but also reduces the hydrogen diffusion rate, which

may have further implications for electronic conductivity and magnetic

dynamo in Uranus and Neptune. Our results were highlighted by Phys.org

|

|

|

Oxygen (red) and hydrogen (blue) atoms in the new H4O structure.

|

Water and hydrogen at high pressure make up a substantial fraction of

the interiors of giant planets. Using ab initio random

structure search methods we investigate the ground-state crystal

structures of water, hydrogen, and hydrogen-oxygen compounds. Here, we find that, at pressures

beyond 14 Mbar, excess hydrogen is incorporated into the ice phase to

form a novel structure with H4O stoichiometry.

We also

predict two new ground state structures of water ice with P21/m

and I4/mmm symmetry to form at 135 and 330 Mbar,

respectively. Here is a slide that summarizes the

seven new high pressure ice phases that were recently predicted with

ab initio calculations.

|

|

|

|

|

|

The four snapshots from our ab initio simulations show how

methane gas at high pressure and temperature forms long hydrocarbon

chains. The blue and white spheres denotes the carbon (C) and hydrogen

atoms, respectively. The red lines indicate the C-C bonds that

increase from left to right. In our recent paper, we show that the resulting

polymeric state is metallic and exists in the interiors of Uranus and

Neptune. We also predict how such a transformation on the atomistic

level can be identified with macroscopic shock wave experiments.

|

|

|

|

|

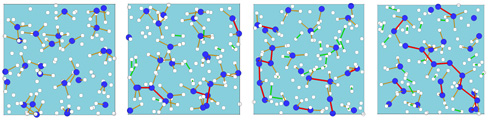

Path integral Monte Carlo simulations are a powerful tool to study

quantum systems at high temperature but applications to elements

beyond hydrogen and helium with core electrons have so far not been possible. In

our recent PRL

article, Kevin Driver and I develop a new all-electron path integral Monte Carlo

technique with free-particle nodes for warm dense matter and apply it

to water and carbon plasmas. Our results for pressures, internal

energies, and pair correlation functions compare well with density

functional molecular dynamics at temperatures of

(2.5-7.5)·105K. Both methods together form a coherent

equation of state over a density-temperature range of 3-12 g/cc and 104-109 K.

|

|

|

|

|

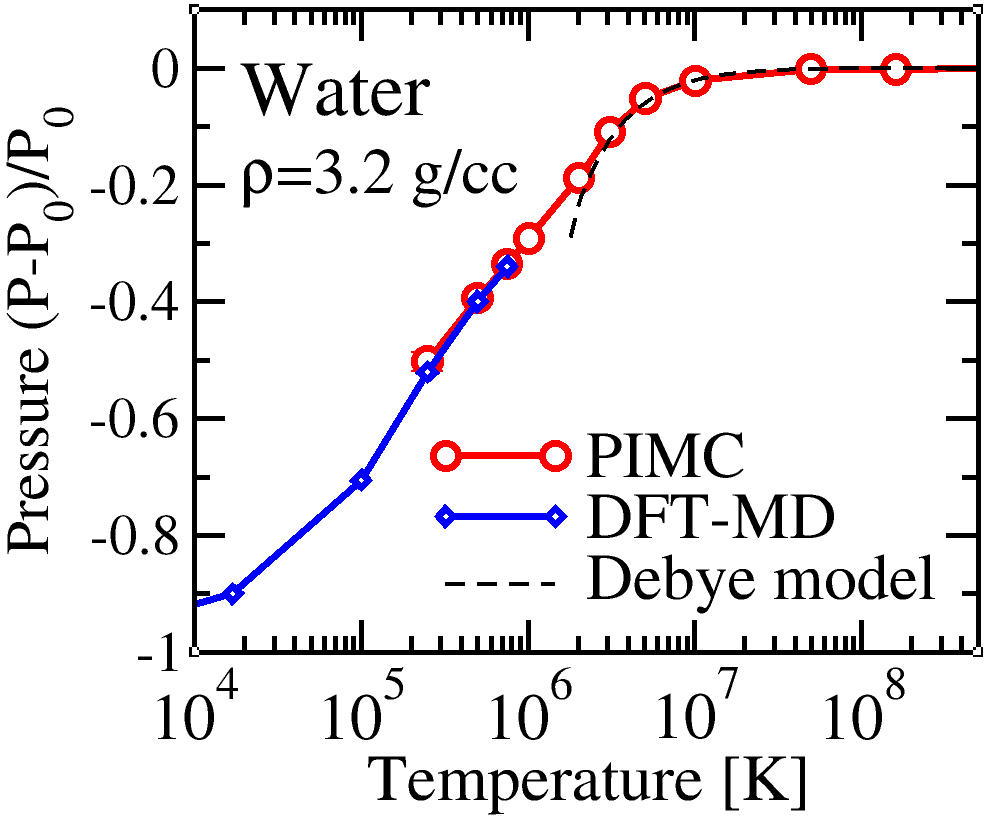

Gas giants are believed to form by the accretion of hydrogen-helium

gas around an initial protocore of rock and ice. The question of

whether the rocky parts of the core dissolve into the layer of

metallic fluid hydrogen following formation has significant

implications for planetary structure and evolution. Here we use ab initio

calculations to study rock solubility in fluid hydrogen, choosing

magnesium oxide as a representative example of planetary rocky

materials, and find MgO to be highly soluble in H for temperatures in

excess of approximately 10000 K, implying significant redistribution

of rocky core material in Jupiter and larger exoplanets.

|

|

|

|

|

Using path integral Monte Carlo simulations we have derived an

equation of state (EOS) table for deuterium that covers typical intertial

confinement fusion conditions at densities ranging from 0.002 to 1596

g/cm3

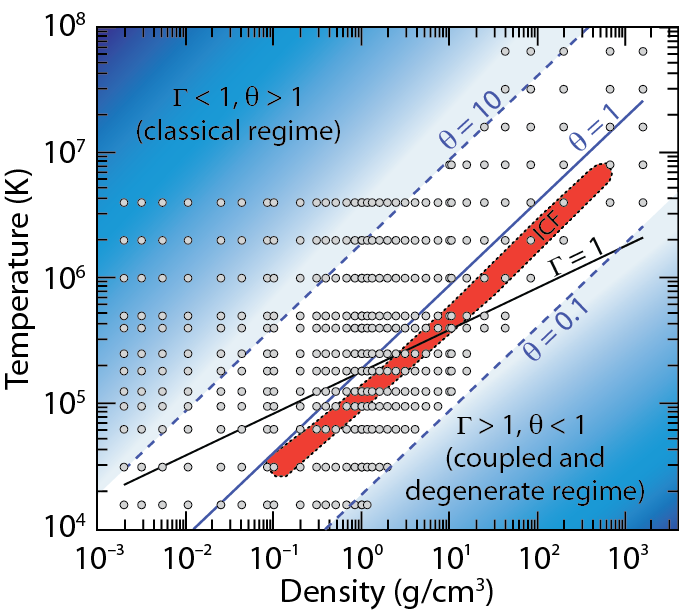

and temperatures of 1.35 eV ~ 5.5 keV. The small grey circles in the

diagram on the left indicate the temperature-density conditions of our

simulations. The EOS and related results are summarized in an article that has been published in Physical Review B.

|

|

|

|

|

The bonding properties of water ice at high pressure are studied in this article. By comparing the Wannier orbitals in the Pnma structure (shown in the image on the left), one can tell that they differ substantially from the sp3

hybridization in the ice X phase at lower pressures. Most strikingly,

the white orbitals are not aligned with any hydrogen bond.

|

|

|

|

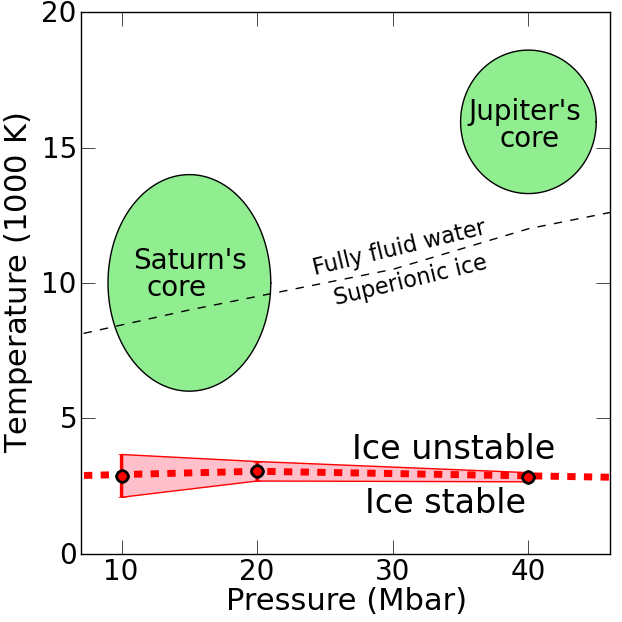

Simulations predict water ice to be unstable above 3000 Kelvin when exposed to metallic hydrogen

|

The four giant planets in our solar system grow so large because icy

comets made their cores grow much faster than those of terrestrial

planets, which enabled them to accrete large amounts of gas. With ab

initio simulations, Hugh Wilson and I demonstrate in our recent manuscript

that water ice is not thermodynamically stable at the temperature and

pressure conditions where core is exposed to the layer of metallic

hydrogen above. This implies that the cores in Jupiter and Saturn have

been eroded over time, with the icy material being redistributed

convectively throughout the planet.

Our work has implications for constraining the interior

structure and evolution of giant planets and will be relevant for the

interpretation of data from NASA's Juno mission to Jupiter (to be launched in

August 2011). Core erosion could also provide a significant flux of

heavy elements to the atmosphere of exoplanets and may explain why

some of them have significantly inflated radii.

|

|

|

|

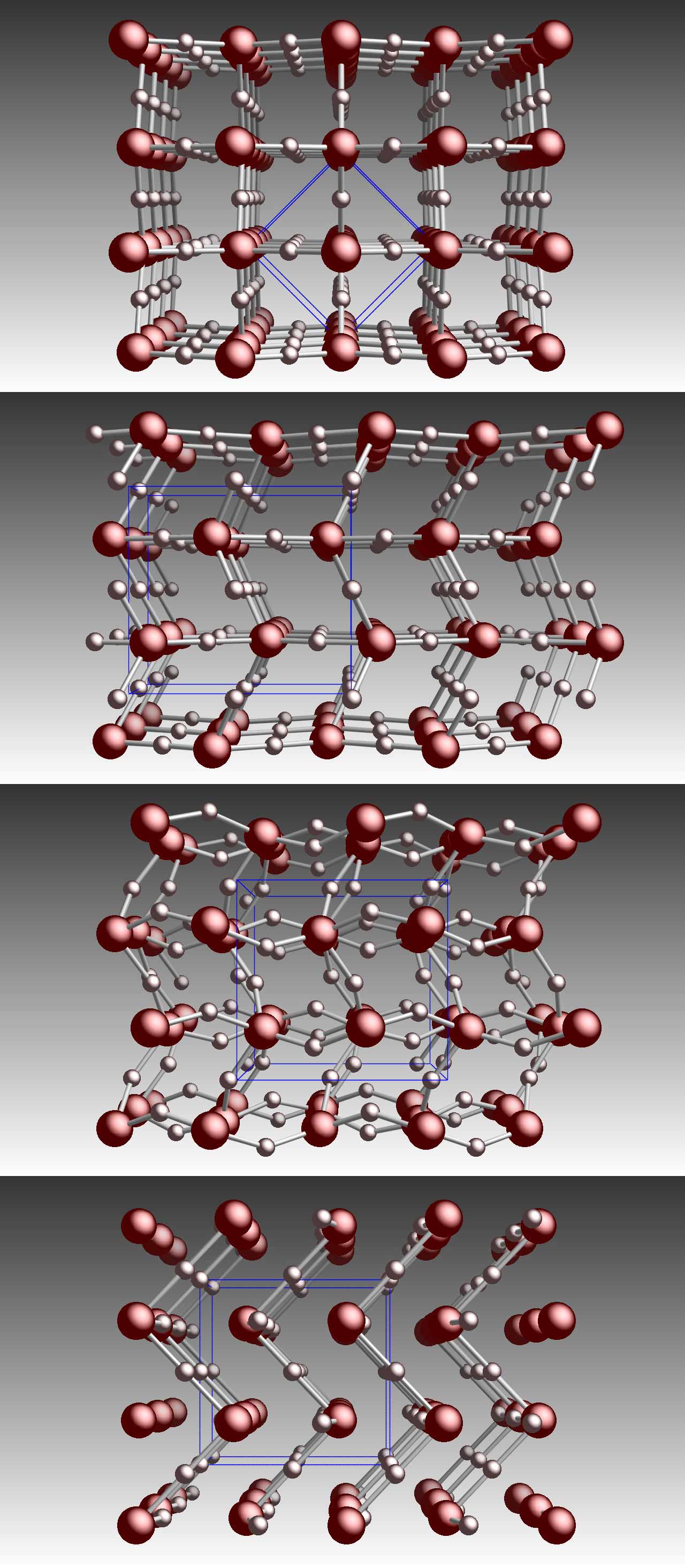

Four high pressure phases of ice

|

Water ice is one of the most prevalent substances in the solar system,

with the majority of it existing at high pressures in the interiors of

giant planets. The known phase diagram of water is extremely rich, with

at least fifteen crystal phases observed experimentally. In our article in Physical Review Letters (see

also cond-mat), Hugh

Wilson and I explore the phase diagram of water ice by means of ab

initio computer simulations and predict two

new phases to occur at megabar pressures. In the figure from

top to bottom, you see

1) ice X the highest pressure phase seen in experiments,

2) the Pbcm phase that was predicted with computer simulations in 1996,

3) our new Pbca phase that transforms out of the Pbcm

phase via a phonon instability at 7.6 Mbar, and finally

4) our new Cmcm structure that is

metallic and predicted to occur at 15.5 Mbar.

The known high pressure ice phases VII, VIII, X and Pbcm as

well as our Pbca phase are all insulating and composed of two

interpenetrating hydrogen bonded networks, but the Cmcm

structure is metallic and consists of corrugated sheets of H and O

atoms. The H atoms are squeezed into octahedral positions between

next-nearest O atoms while they occupy tetrahedral positions between

nearest O atoms in the ice X, Pbcm, and Pbca phases.

|

|

|

|

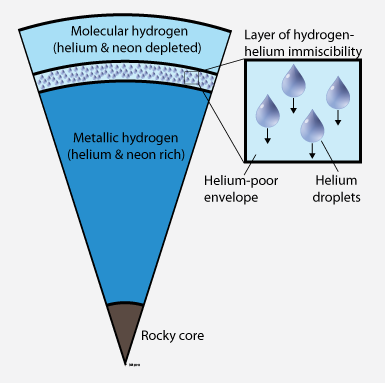

Jupiter’s interior. Helium rain occurs in the immiscibility layer and depletes the upper layer of both helium and neon.

|

When the Galileo entry

probe entered Jupiter's atmosphere in 1995, it measured that

the inert gas neon was depleted by a

factor of 10 compared to the composition of sun, which represents the

concentrations in nebula that formed our solar system with all its

eight planets. So where is all the neon gone that was present in

Jupiter initially? Using ab initio computer

simulations Hugh Wilson and I link the missing neon to another

process that was proposed to occur inside Jupiter: helium

rain.

There is indirect evidence from luminosity measurements that helium

rain occurs on Saturn but it was unclear whether it occurs inside

Jupiter also. Our calculations now show that neon preferentially

dissolves into helium droplets and it is therefore gradually sequestered

into the deeper interior as the helium rain falls. The remaining hydrogen-rich envelope is

slowly depleted of both neon and helium. The measured concentrations

of both elements agree quantitatively with our calculations.

Read commentary by J. Fortney "Peering into Jupiter", UC Berkeley's press release, Discovery Channel and LA Times articles.

|

|

|

|

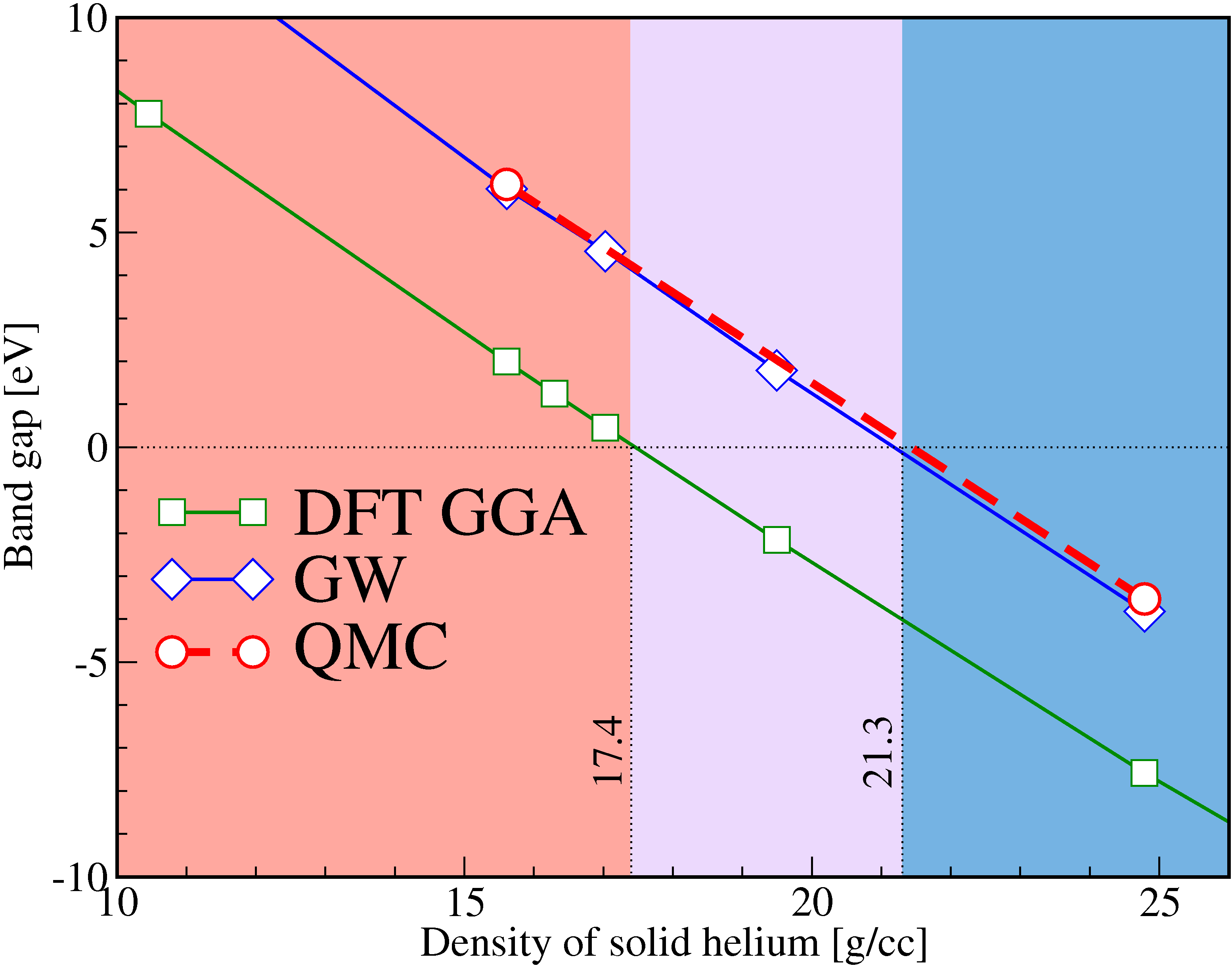

Insulator-to-Metal Transition in Solid Helium at High Pressure

|

Metallic solid helium is present in the outer layers of White Dwarf

stars. The cooling rate of White Dwarfs is regulated by the heat flow

from the hot interior to the colder exterior. The

insulator-to-metal transition is of interest because it marks the

point where heat transport switches from electronic

conductions to photon diffusion. In our paper, the

insulator-to-metal transition in solid helium at high pressure is

studied with different first-principles simulations. Diffusion quantum

Monte Carlo (QMC) calculations predict that the band gap closes at a

density of 21.3 g/cc and a pressure of 25.7 terapascals, which is 20%

higher in density and 40 higher in pressure than predicted by standard

density functional calculations. The metallization density derived

from GW calculations is found to be in very close agreement with QMC

predictions. Path integral Monte Carlo calculations showed that

the zero-point motion of the nuclei has no significant effect on the

metallization transition.

|

| |

|

Helium in molecular hydrogen

|

Helium in metallic hydrogen

|

We performed density functional molecular dynamics simulation to

characterize hydrogen-helium mixtures in the interior of solar and

extrasolar giant planets. In this

article, we address outstanding questions about their structure

and evolution e.g. whether Jupiter has a rocky core and if it was

formed by a core accretion process. We describe how the presence of

helium defers the molecular-to-metallic transition in hydrogen to

higher pressures by stabilizing hydrogen molecules.

| |

|

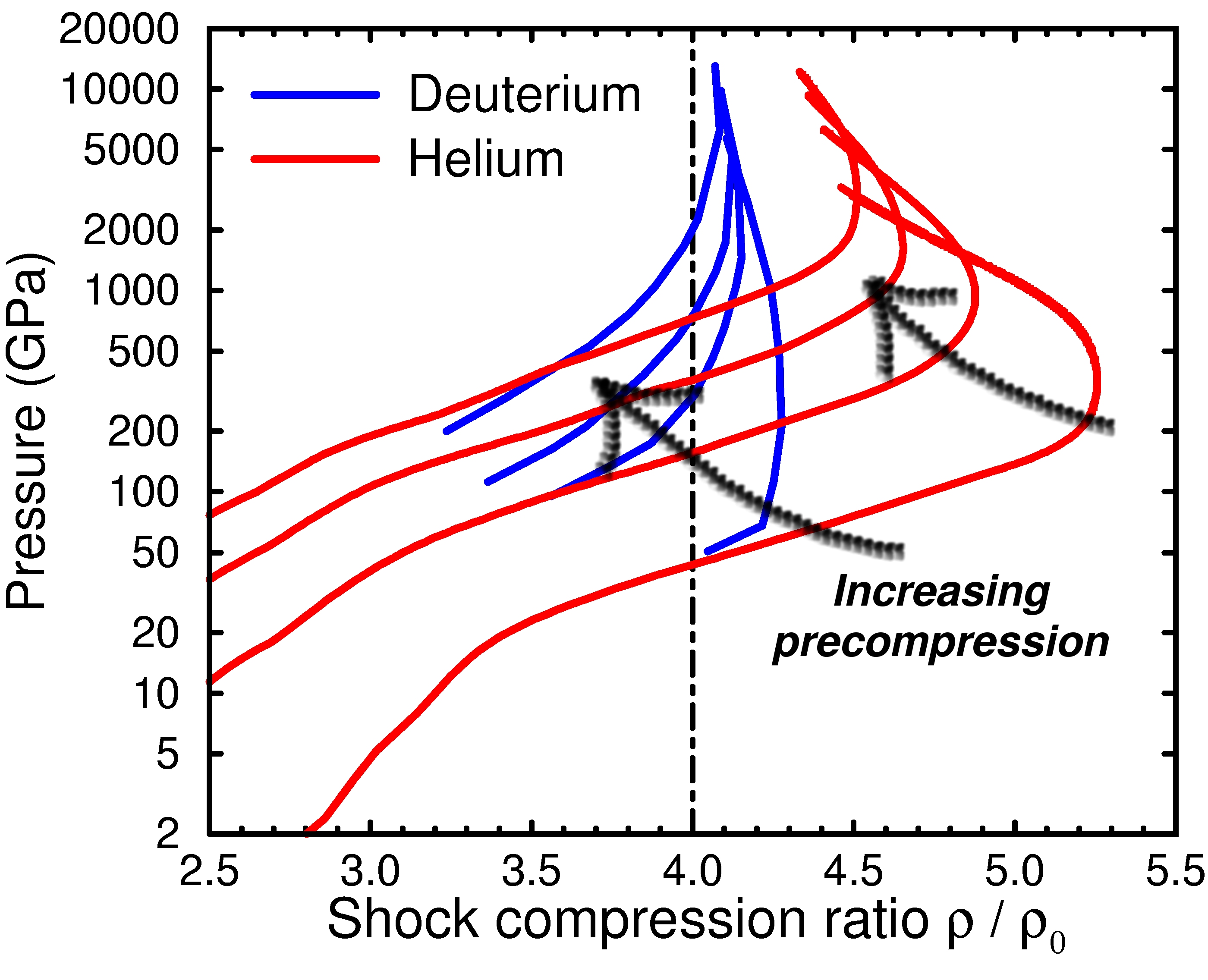

Shock hugoniot curves for precompressed hydrogen and helium.

|

Shock wave experiments allow one to study a material's properties at

high pressure and temperature. In this

article, we

used first-principles computer simulation to predict the properties of

shock fluid helium at megabar pressures. The simulations show that the

compressibility of helium is substantially increased by electronic

excitations. A maximum compression ratio of 5.24-fold the initial

density was predicted for 360 GPa and 150000 K. This result

distinguishes helium from deuterium, for which simulations predicted a

maximum compression ratio of 4.3. If the sample are precompressed

statically the compression ratio is reduced, which is shown in the

left graph.

|

| |

|

Spin fluctuations present molecular oxygen (left) are suppressed at high pressures (right).

|

In recent shock wave experiments [Phys. Rev. Lett. 86, 3108 (2001)],

the conductivity of liquid oxygen was measured for pressures up to 1.8

Mbar and indications for a insulator-metal transition were found.

In this article, we report

results from density functional molecular dynamics simulations of dense liquid oxygen

close to the metal-insulator transition. We have

found that band gap closure occurs in the molecular liquid, with a

slow transition from a semi-conducting to a poor metallic state

occurring over a wide pressure range. At approximately 80 GPa,

molecular dissociation is observed in the metallic fluid. Spin

fluctuations play a key role in determining the electronic structure

of the low pressure fluid, while they are suppressed at high pressure.

|

| |

|

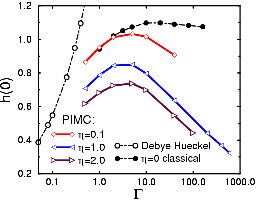

Many-body enhancement of nuclear reaction rates h(0) as function of the coupling parameter.

Many-body enhancement of nuclear reaction rates h(0) as function of the coupling parameter.

|

Dense plasma effects can cause an exponenial change in charge particle

nuclear reaction rates important in stellar evolution.

In this article, reaction rates

in dense plasmas are examined using path integral Monte Carlo. Quantum

effects causes a reduction in the many body enhancement of the

reaction rate, h(0), compared to the classical value. This is shown in

figure on the left for different quantum parameters. This reduction

can be attributed to the "quantum smearing" of the Coulomb interaction

at the short range resulting in a reduced repulsion between the

reacting pair and surrounding particles.

|

| |

|

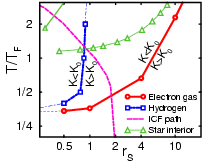

Temperature density region of kinetic energy lowering for dense hydrogen and the electron gas.

Temperature density region of kinetic energy lowering for dense hydrogen and the electron gas.

|

The equilibrium momentum distribution is of fundamental importance to

characterize many-body systems. In contrast to classical systems where

the distribution is always Maxwellian, in quantum systems the

distribution depends on particle statistics, bosons or fermions, as

well as on interactions and can display interparticle correlations,

which are the basis of superfluidity and superconductivity.

In this article, we

report and explain a surprising effect of interactions in quantum

systems on the one particle momentum distribution and kinetic

energy. Interactions never lower the ground state kinetic energy of a

quantum system. However, at nonzero temperature, where the system

occupies a thermal distribution of states, interactions can reduce the

kinetic energy below the noninteracting value. This is

demonstrated using PIMC simulations for dense hydrogen and the electron gas.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Molecular liquid |

Molecular metallic liquid |

Metallic liquid |

|

|

|

At which pressure and density does hydrogen become metallic?

At which pressure and density does hydrogen become metallic?

|

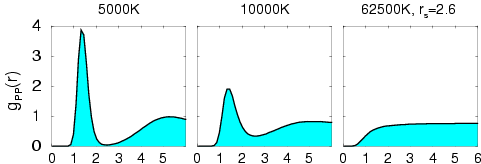

At low densities up to about rs=2.6, the properties of hydrogen including

the equation of state are well understood. Processes like the thermal dissociation of molecules

can be modelled accurately with PIMC. The resulting proton-proton pair correlation functions are shown.

At low densities up to about rs=2.6, the properties of hydrogen including

the equation of state are well understood. Processes like the thermal dissociation of molecules

can be modelled accurately with PIMC. The resulting proton-proton pair correlation functions are shown.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 157. |

J. Vorberger and 73 co-authors including B. Militzer, "Roadmap for warm dense matter physics",

submitted for publication (2025). Available on the arXiv.

|

| 156. |

K. de Villa, F. Gonzalez-Cataldo, B. Militzer, "Experimental Pathways for Detecting Double Superionicity in Planetary Ices",

Contributions to Plasmas Physics, in press (2025). DOI: 10.1002/ctpp.70015 Available on the arXiv.

|

| 155. |

B. Militzer, "Ensemble Monte Carlo Calculations with Five Novel Moves",

Computer Physics Communications 309 (2025) 109424. Our C++ source code is available at DOI 10.5281/zenodo.13961174

and the manuscripts on the arXiv.

|

| 154. |

B. Militzer, "Phase Separation of Planetary Ices Explains Nondipolar Magnetic Fields of Uranus and Neptune",

Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 121 (2024) e2403981121. DOI: 10.1073/pnas.240398112.

|

| 153. |

A.C. Li, B. Li, F. Gonzalez-Cataldo, R.E. Rudd, B. Militzer, E.M. Bringae, M.A. Meyers, "Diamond under extremes",

Materials Science & Engineering R 161 (2024) 100857. DOI: 10.1016/j.mser.2024.100857

|

| 152. |

X. Wang, N. Geng, K. de Villa, B. Militzer, E. Zurek, "Superconductivity in Dilute Hydrides of Ammonia under Pressure",

Physical Chemistry Letters 15 (2024) 5947. DOI: 10.1021/acs.jpclett.4c01223

|

| 151. |

M. Bonitz, J. Vorberger, M. Bethkenhagen, M. P. Bohme, D. M. Ceperley, A. Filinov, F. Graziani, G. Gregori, P. Hamann, S. B. Hansen, M. Holzmann, S. Hu, H. Kahlert, V. Karasiev, U. Kleinschmidt, L. Kordts, C. Makait, B. Militzer, Z. A. Moldabekov, C. Pierleoni, M. Preising, K. Ramakrishna, R. Redmer, S. Schwalbe, P. Svensson, T. Dornheim, "First principles simulations of dense hydrogen", Physics of Plasmas 31 (2024) 110501. DOI 10.1063/5.0219405 Available on the arXiv.

|

| 150. |

B. Militzer, W. B. Hubbard,

"Study of Jupiter's Interior: Comparison of 2, 3, 4, 5, and 6 Layer Models",

Icarus 411 (2024) 115955. DOI 10.1016/j.icarus.2024.115955. Our models for Jupiter's interior are available as a machine readable file mrt_files_05-28-23.tgz and also on 10.5281/zenodo.10471389. Available on the arXiv.

|

| 149. |

K. de Villa, F. Gonzalez-Cataldo, B. Militzer,

"Double Superionicity in Icy Compounds at Planetary Interior Conditions",

Nature Communications 14 (2023) 7580. DOI 10.1038/s41467-023-42958-0. Highlighted by Nat. Comm. editor and in this NERSC article.

|

| 148. |

H. Cao, J. Bloxham, R. S. Park, B. Militzer, R. K. Yadav, L. Kulowski, D. J. Stevenson, S. J. Bolton,

"Strong resemblance between surface and deep zonal winds inside Jupiter revealed by high-degree gravity moments",

Astrophysical Journal 959 (2023) 78. DOI: 10.3847/1538-4357/ad0cbb. Available on the arXiv.

|

| 147. |

F. Gonzalez-Cataldo, B. Militzer,

"Ab initio determination of iron melting at terapascal pressures and Super-Earths core crystallization",

Physical Review Research 5 (2023) 033194. DOI: 10.1103/PhysRevResearch.5.033194. EOS tables for the solid phase and the liquid phase.

|

| 146. |

B. Militzer,

"Study of Jupiter's Interior with Quadratic Monte Carlo Simulations",

Astrophysical J. 953 (2023) 111. DOI: 10.3847/1538-4357/ace1f1 Here we provide our open QMC source code. Available on the arXiv. Data files for different interior models and gravity harmonics:

1a,

1b,

2a,

2b,

3a and

3b.

|

| 145. |

F. Gonzalez-Cataldo, B. Militzer,

"Structural and Thermodynamic Properties of Magnesium-Rich Liquids at Ultrahigh Pressure",

Minerals 13 (2023) 885. DOI: 10.3390/min13070885.

|

| 144. |

B. Militzer, W. B. Hubbard,

"Relation of Gravity, Winds, and the Moment of Inertia of Jupiter and Saturn",

Planet. Sci. J. 4 (2023) 95. DOI: 10.3847/PSJ/acd2cd Available on the arXiv

|

| 143. |

T. Kovacevic, F. Gonzalez-Cataldo, B. Militzer,

"The homogeneous mixing of MgO and H2O at extreme conditions",

Contrib. Plasma Phys. (2023) e202300017. DOI: 10.1002/ctpp.202300017

|

| 142. |

S. Howard, T. Guillot, M. Bazot, Y. Miguel, D. J. Stevenson, E. Galanti, Y. Kaspi, W. B. Hubbard, B. Militzer, R. Helled, N. Nettelmann, B. Idini, and S. Bolton,

"Jupiter's Interior from Juno: Equations of State Uncertainties and Dilute Core Extent", Astronomy and Astrophysics 672 (2023) A33.

| | 141. |

K. M. Moore, A. Barik, S. Stanley, D. J. Stevenson, N. Nettelmann, R. Helled, T. Guillot, B. Militzer, S. Bolton,

"Dynamo Simulations of Jupiter's Magnetic Field: The Role of Stable Stratification and a Dilute Core",

JGR Planets 127 (2022) e2022JE007479.

|

| 140. |

J. Wisdom, R. Dbouk, B. Militzer, W. B. Hubbard, F. Nimmo, B. Downey, R. French,

"Loss of a satellite could explain Saturn's obliquity and young rings",

Science 377 (2022) 1285.

|

| 139. |

B. Militzer, W.B. Hubbard, S. Wahl, J.I. Lunine, E. Galanti, Y. Kaspi, Y. Miguel, T. Guillot, K. M. Moore, M. Parisi, J.E.P. Connerney, R. Helled, H. Cao, C. Mankovich, D. J. Stevenson, R. S. Park, M. Wong, S. K. Atreya, J. Anderson, S.J. Bolton,

"Juno Spacecraft Measurements of Jupiter's Gravity Imply a Dilute Core",

Planet. Sci. J. 3 (2022) 185. Data file for interior model.

|

| 138. |

T. Kovacevic, F. Gonzalez-Cataldo, S. T. Stewart, B. Militzer,

"Miscibility of rock and ice in the interiors of water worlds",

Scientific Reports 12 (2022) 13055.

|

| 137. |

R. Helled, D.J. Stevenson, J.I. Lunine, S.J. Bolton, N. Nettelmann, S. Atreya, T. Guillot, B. Militzer, Y. Miguel, W.B. Hubbard,

"Revelations on Jupiter's Formation, Evolution and Interior: Challenges from Juno Results",

Icarus 378 (2022) 114937.

|

| 136. |

Y. Miguel, M. Bazot, T. Guillot, S. Howard, E. Galanti, Y. Kaspi, W. B. Hubbard, B. Militzer, R. Helled, S. K. Atreya, J. E. P. Connerney, D. Durante, L. Kulowski, J. I. Lunine, D. Stevenson, S. Bolton,

"Jupiter's inhomogeneous envelope", Astronomy and Astrophys. 662 (2022) A18.

| | 135. |

Y.-J. Kim, B. Militzer, B. Boates, S, Bonev, P.M. Celliers, G.W. Collins, K.P. Driver, D.E. Fratanduono, S. Hamel, R. Jeanloz, J.R. Rygg, D.C. Swift, J.H. Eggert, M. Millot,

"Evidence for Dissociation and Ionization in Shock Compressed Nitrogen to 800 GPa",

Phys. Rev. Lett. 129 (2022) 015701.

|

| 134. |

J. Wu, F. Gonzalez-Cataldo, F. Soubiran, B. Militzer,

"The phase diagrams of beryllium and magnesium oxide at megabar pressures",

J. Phys. Cond. Matt. 34 (2022) 144003.

|

| 133. |

R. Akiba, A. Ermakov, B. Militzer,

"Probing the icy shell structure of ocean worlds with gravity-topography admittance",

Planetary Science J. 3 (2022) 53.

|

| 132. |

A. E. Gleason, D. R. Rittman, C. A. Bolme, E. Galtier, H. J. Lee, E. Granados, S. Ali, A. Lazicki, D. Swift, P. Celliers, B. Militzer, S. Stanley, W.L. Mao,

"Dynamically compressed water to 200 GPa: implications for ice giant interiors",

Science Advances 12 (2022) 715.

|

| 131. |

T. Dornheim, Z. A. Moldabekov, J. Vorberger, B. Militzer,

"Path Integral Monte Carlo Approach to the Structural Properties and Collective Excitations of liquid 3He without Fixed Nodes",

Scientific Reports 12 (2022) 708.

|

| 130. |

F. Gonzalez-Cataldo, B.K. Godwal, K. Driver, R. Jeanloz, B. Militzer,

"A Model of Ramp Compression of Diamond from Ab Initio Simulations",

Phys. Rev. B 104 (2021) 134104. DOI: 10.1103/PhysRevB.104.134104

|

| 129. |

S. M. Wahl, D. Thorngren, T. Lu, B. Militzer,

"Tidal Response and Shape of Hot Jupiters",

Astrophysical J. 921 (2021) 105. DOI: 10.3847/1538-4357/ac1a72 Available on the arXiv

|

| 128. |

T. Dornheim, M. Boehme, B. Militzer, J. Vorberger,

"Momentum distribution of the Uniform Electron Gas at finite temperature: Effects of spin-polarization",

Phys. Rev. E 104 (2021) 055205. DOI: 10.1103/PhysRevE.104.055206. Available on the arXiv.

|

| 127. |

J. Wu, F. Gonzalez-Cataldo, B. Militzer,

"High Pressure Phase Diagram of Beryllium from Ab Initio Free Energy Calculations",

Phys. Rev. B 104 (2021) 014103. DOI: 10.1103/PhysRevB.104.014103. Available on the arXiv.

|

| 126. |

T. Dornheim, M. Boehme, B. Militzer, J. Vorberger,

"Ab initio path integral Monte Carlo approach to the momentum distribution of the uniform electron gas at finite temperature without fixed nodes",

Phys. Rev. B 103 (2021) 205142. DOI: 10.1103/PhysRevB.103.205142. Available on the arXiv.

|

| 125. |

G. Massacrier, M. Boehme, J. Vorberger, F. Soubiran, B. Militzer,

"Reconciling Ionization Energies and Band Gaps of Warm Dense Matter Derived with Ab Initio Simulations and Average Atom Models",

Phys. Rev. Res. 3 (2021) 023026. DOI: 10.1103/PhysRevResearch.3.023026.

|

| 124. |

H. D. Whitley, G. E. Kemp, C. Yeamans, Z. Walters, B. E. Blue, W.Garbett, M. Schneider, R. S. Craxton, E. M. Garcia, P. W. McKenty, M. Gatu-Johnson, K. Caspersen, J. I. Castor, M. Dane, C. L. Ellison, J. Gaffney, F. R. Graziani, J. Klepeis, N. Kostinski, A. Kritcher, B. Lahmann, A. E. Lazicki, H. P. Le, R. A. London, B. Maddox, M. Marshall, M. E. Martin, B. Militzer, A. Nikroo, J. Nilsen, T. Ogitsu, J. Pask, J. E. Pino, M. Rubery, R. Shepherd, P. A. Sterne, D. C. Swift, L. Yang, S. Zhang

"Comparison of ablators for the polar direct drive exploding pusher platform",

J. High Energy Density Physics 38 (2021) 100928. DOI: 10.1016/j.hedp.2021.100928 Available on the arXiv.

|

| 123. |

B. Militzer, F. Gonzalez-Cataldo, S. Zhang, K. P. Driver, F. Soubiran,

"First-principles equation of state database for warm dense matter computation",

Phys. Rev. E 103 (2021) 013203. DOI: 10.1103/PhysRevE.103.013203 Available on the arXiv. Click here to reach our FPEOS webpage.

|

| 122. |

R. Domingos, M. M. Tremblay, D. L. Shuster, B. Militzer,

"Simulations and experiments reveal effect of nanopores on helium diffusion in quartz",

ACS Earth and Space Chemistry 4 (2020) 1906. DOI: 10.1021/acsearthspacechem.0c00187

|

| 121. |

B. Militzer, F. Gonzalez-Cataldo, S. Zhang, H. D. Whitley, D. C. Swift, M. Millot,

"Nonideal Mixing Effects in Warm Dense Matter Studied with First-Principles Computer Simulations",

J. Chem. Phys. 153 (2020) 184101. DOI: 10.1063/5.0023232. Available on the arXiv.

|

| 120. |

F. Soubiran, B. Militzer,

"Anharmonicity and Phase Diagram of Magnesium Oxide in the Megabar Regime",

Phys. Rev. Lett. 125 (2020) 175701. DOI: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.125.175701.

|

| 119. |

F. Gonzalez-Cataldo, F. Soubiran, B. Militzer,

"Equation of State of Hot, Dense Magnesium Derived with First-Principles Computer Simulations",

Physics of Plasmas 27 (2020) 092706. DOI: 10.1063/5.0017555. Available on the arXiv.

| | 118. |

M. A. Olson, S. Bhatia, P. Larson, B. Militzer,

"Prediction of Chlorine and Fluorine Crystal Structures at High Pressure Using Symmetry Driven Structure Search with Geometric Constraints",

J. Phys. Chem. 153 (2020) 094111. Available on the arXiv.

| | 117. |

S. Zhang, M. C. Marshall, L. H. Yang, P. A. Sterne, B. Militzer, M. Daene, J. A. Gaffney, A. Shamp, T. Ogitsu, K. Caspersen, A. E. Lazicki, D. Erskine, R. A. London, P. M. Celliers, J. Nilsen, H. D. Whitley,

"Benchmarking boron carbide equation of state using computation and experiment",

Phys. Rev. E 102 (2020) 053203. Available on the arXiv.

| | 116. |

F. Gonzalez-Cataldo, B. Militzer,

"Thermal and Pressure Ionization in Warm, Dense MgSiO3 Studied with First-Principles Computer Simulations",

AIP Conference Proceedings 2272 (2020) 090001. DOI: 10.1063/12.0000793. Available on the arXiv.

| | 115. |

S. M. Wahl, M. Parisi, W. M . Folkner, W. B. Hubbard, B. Militzer,

"Equilibrium Tidal Response of Jupiter: Detectability by Juno Spacecraft",

Astrophys. J. 891:42 (2020) 1 (DOI).

| | 114. |

M. Millot, S. Zhang, D. E. Fratanduono, F. Coppari, S. Hamel, B. Militzer, D. Simonova, S. Shcheka, N. Dubrovinskaia, L. Dubrovinsky, J. H. Eggert,

"Recreating giants impacts in the laboratory: Shock compression of MgSiO3 bridgmanite to 14 Mbar",

Geophys. Res. Lett. 47 (2020) e2019GL085476.

| | 113. |

F. Gonzalez-Cataldo, F. Soubiran, H. Peterson, B. Militzer,

"Path Integral Monte Carlo and Density Functional Molecular Dynamics Simulations of Warm, Dense MgSiO3",

Phys. Rev. B 101 (2020) 024107. Available on the arXiv.

| | 112. |

F. Soubiran, F. Gonzalez-Cataldo, K. P. Driver, S. Zhang, B. Militzer,

"Magnesium Oxide at Extreme Temperatures and Pressures Studied with First-Principles Simulations",

J. Chem. Phys. 151 (2019) 214104.

| | 111. |

B. Militzer, S. Wahl, W. B. Hubbard,

"Models of Saturn's Interior Constructed with an Accelerated Concentric Maclaurin Spheroid Method",

Astrophysical Journal 879 (2019) 78. Available on the arXiv.

| | 110. |

S. Zhang, A. Lazicki, B. Militzer, L. H. Yang, K. Caspersen, J. A. Gaffney, M. W. Däne, J. E. Pask, W. R. Johnson, A. Sharma, P. Suryanarayana, D. D. Johnson, A. V. Smirnov, P. A. Sterne, D. Erskine, R. A. London, F. Coppari, D. Swift, J. Nilsen, A. J. Nelson, H. D. Whitley, "Equation of state of warm-dense boron nitride combining computation, modeling, and experiment", Phys. Rev. B 99 (2019) 165103. Available on the arXiv.

| | 109. |

L. Iess, B. Militzer, Y. Kaspi, P. Nicholson, D. Durante, P. Racioppa, A. Anabtawi, E. Galanti, W. Hubbard, M. J. Mariani, P. Tortora, S. Wahl, M. Zannoni,

"Measurement and implications of Saturn's gravity field and ring mass", Science 17 Jan 2019:eaat2965. DOI: 10.1126/science.aat2965.

| | 108. |

B. Militzer, E. L. Pollock, D. Ceperley,

"Path Integral Monte Carlo Calculation of the Momentum Distribution of the Homogeneous Electron Gas at Finite Temperature", J. High Energy Density Physics 30 (2019) 13-20.

| | 107. |

R. Domingos, K. M. Shaik, B. Militzer,

"Prediction of Novel High Pressure H2O-NaCl and Carbon Oxide Compounds with Symmetry-Driven Structure Search Algorithm", Phys. Rev. B 98 (2018) 174107. Also available on the arXiv. |

| 106. |

F. Soubiran, B. Miltzer,

"Electrical conductivity and magnetic dynamos in magma oceans of Super-Earths",

Nature Communications 9 (2018) 3883. |

| 105. |

S. Zhang, B. Militzer, M. C. Gregor, K. Caspersen, L. H. Yang, T. Ogitsu, D. Swift, A. Lazicki, D. Erskine, R. A. London, P. M. Celliers, J. Nilsen, P. A. Sterne, and H. D. Whitley

"Theoretical and experimental investigation of the equation of state of boron plasmas",

Phys. Rev. E 98 (2018) 023205, available on the arXiv. |

| 104. |

K. P. Driver, F. Soubiran, B. Militzer,

"Path integral Monte Carlo simulations of hot, dense aluminum",

Physical Review E 97 (2018) 063207.

|

| 103. |

L. Iess, W. M. Folkner, D. Durante, M. Parisi, Y. Kaspi, E. Galanti,

T. Guillot, W. B. Hubbard, D. J. Stevenson, J. D. Anderson,

D. R. Buccino, L. Gomez Casajus, A. Milani, R. Park, P. Racioppa,

D. Serra, P. Tortora, M. Zannoni, H. Cao, R. Helled, J. I. Lunine,

Y. Miguel, B. Militzer, S. Wahl, J. E. P. Connerney, S. M. Levin,

S. J. Bolton,

"Measurement

of Jupiter's asymmetric gravity field",

Nature 555 (2018) 220. |

| 102. |

Y. Kaspi, E. Galanti, W. B. Hubbard, D. J. Stevenson, S. J. Bolton,

L. Iess, T. Guillot, J. Bloxham, J. E. P. Connerney, H. Cao,

D. Durante, W. M. Folkner, R. Helled, A. P. Ingersoll, S. M. Levin,

J. I. Lunine, Y. Miguel, B. Militzer, M. Parisi, S. M. Wahl

"Jupiter's

atmospheric jet streams extend thousands of kilometres deep",

Nature 555 (2018) 223. |

| 101. |

T. Guillot, Y. Miguel, B. Militzer, W. B. Hubbard, Y. Kaspi,

E. Galanti, H. Cao, R. Helled, S. M. Wahl, L. Iess, W. M. Folkner,

D. J. Stevenson, J. I. Lunine, D. R.

Reese, A. Biekman, M. Parisi,

D. Durante, J. E. P. Connerney, S. M. Levin & S. J. Bolton,

"A suppression

of differential rotation in Jupiter's deep interior", Nature 555 (2018) 227. |

| 100. |

B. Militzer, S. Zhang,

"Ab initio Simulations of Superionic H2O, H2O2, and H9O4 Compounds",

AIP conference proceedings 1979 (2018) 050012. Also available on the arXiv. |

| 99. |

S. Zhang, B. Militzer, L. X. Benedict, F. Soubiran, K. P. Driver, P. A. Sterne,

"Path integral Monte Carlo simulations of dense carbon-hydrogen plasmas",

J. Chem. Phys. 148 (2018) 102318. Also available on the arXiv. |

| 98. |

Y. Kaspi, T. Guillot, E. Galanti, Y. Miguel, R. Helled, W. B. Hubbard, B. Militzer, S. M. Wahl, S. Levin, J. E. P. Connerney, S. J. Bolton,

"The effect of differential rotation on Jupiter's low-degree even gravity moments",

Geophysical Research Letters 44 (2017) 5960, doi:10.1002/2017GL073629.

|

| 97. |

S. Zhang, K. P. Driver, F. Soubiran, B. Militzer

"First-principles Equation of State and Shock Compression Predictions of Warm Dense Hydrocarbons",

Phys. Rev. E 96 (2017) 013204. |

| 96. |

K. P. Driver, B. Militzer,

"First-principles simulations of warm dense lithium fluoride",

Phys. Rev. E 95 (2017) 043205.

Also availalbe on the arXiv. |

| 95. |

S. M. Wahl, W. B. Hubbard, B. Militzer, T. Guillot, Y. Miguel, Y. Kaspi, R. Helled, D. Reese, N. Movshovitz, E. Galanti, S. Levin, J.E. Connerney, S.J. Bolton,

"Comparing Jupiter interior structure models to Juno gravity measurements and the role of a dilute core",

Geophysical Research Letters 44 (2017) 4649, doi:10.1002/2017GL073160.

|

| 94. |

K. P. Driver, F. Soubiran, S. Zhang, B. Militzer,

"Comparison of Path Integral Monte Carlo Simulations of Helium, Carbon, Nitrogen, Oxygen, Water, Neon, and Silicon Plasmas",

J. High Energy Density Physics 23 (2017) 81.

|

| 93. |

F. Soubiran, B. Militzer, K. P. Driver, S. Zhang,

"Properties of hydrogen, helium, and silicon dioxide mixtures in giant planet interiors",

Physics of Plasmas 24 (2017) 041401. Also available on the arXiv.

|

| 92. |

S. Zhang, K. P. Driver, F. Soubiran, B. Militzer,

"Equation of state and shock compression of warm dense sodium - A first-principle study",

J. Chem. Phys. 146 (2017) 074505. Also available on the arXiv.

|

| 91. |

T. Leonhardi, B. Militzer,

"Ab initio simulations of liquid carbon monoxide at high pressure",

J. High Energy Density Physics 22 (2017) 41.

|

| 90. |

Z. Li, J. Li, L. Rebecca, J. Liu, B. Militzer,

"Determination of calcium carbonate and sodium carbonate melting curves up to Earth's transition zone pressures with implications for the deep carbon cycle",

Earth and Planetary Science Letters 457 (2017) 395.

|

| 89. |

S. Zhang, K. P. Driver, F. Soubiran, B. Militzer,

"Path Integral Monte Carlo Simulations of Warm Dense Sodium",

J. High Energy Density Physics 21 (2016) 16.

|

| 88. |

B. Militzer,

"Supercell Design for First-Principles Simulations of Solids and Application to Diamond, Silica, and Superionic Water",

J. High Energy Density Physics 21 (2016) 8.

|

| 87. |

S. X. Hu, B. Militzer, L. A. Collins, K. P. Driver, and J. D. Kress,

"First-Principles Prediction of the Softening of the Silicon Shock Hugoniot Curve",

Phys. Rev. B 94 (2016) 094109. Also available on the arXiv. |

| 86. |

B. Militzer, F. Soubiran, S. M. Wahl, W. Hubbard,

"Understanding Jupiter's Interior",

J. Geophysical Research, 121 (2016) 1552. Also available on the arXiv. |

| 85. |

S. M. Wahl, W. B. Hubbard, B. Militzer,

"Tidal response of preliminary Jupiter model",

Astrophysical J. 831 (2016) 14. Also available on the arXiv. |

| 84. |

F. Soubiran, B. Militzer,

"The properties of heavy elements in giant planet envelopes",

Astrophysical J. 829 (2016) 14. Also available on the arXiv.

| | 83. |

B. Militzer,

"Computation of the High Temperature Coulomb Density Matrix in Periodic Boundary Conditions", Computer Physics Communications 204 (2016) 88. Also available on the

arXiv.

| | 82. |

S. M. Wahl, W. B. Hubbard, B. Militzer,

"The Concentric Maclaurin Spheroid method with tides and a rotational enhancement of Saturn's tidal response",

Icarus 282 (2017) 183. Also available on the arXiv. |

| 81. |

W. B. Hubbard, B. Militzer,

"A preliminary Jupiter model",

Astrophysical Journal 820 (2016) 80.

Also available on the arXiv. |

| 80. |

K. P. Driver, B. Militzer,

"First-Principles Equation of State Calculations of Warm Dense Nitrogen",

Phys. Rev. B 93 (2016) 064101. |

| 79. |

S. Zhang, S. Cottaar, T. Liu, S. Stackhouse, B. Militzer,

"High-pressure, temperature elasticity of Fe- and Al-bearing MgSiO3: implications for the Earth's lower mantle",

Earth and Planetary Science Letters 434 (2016) 264. |

| 78. |

B. Militzer, K. P Driver,

"Development of Path Integral Monte Carlo Simulations with Localized Nodal Surfaces for Second-Row Elements",

Phys. Rev. Lett. 115 (2015) 176403. |

| 77. |

K. P. Driver, F. Soubiran, Shuai Zhang, and B. Militzer

"First-principles equation of state and electronic properties of warm dense oxygen",

J. Chem. Phys. 143 (2015) 164507. |

| 76. |

F. Soubiran, B. Militzer,

"Miscibility calculations for water and hydrogen in giant planets",

Astrophys. J. 806 (2015) 228. |

| 75. |

S. X. Hu, V. N. Goncharov, T. R. Boehly, R. L. McCrory, S. Skupsky, L. A. Collins, J. D. Kress, B. Militzer,

"Impact of First-Principles Properties of Deuterium-Tritium on Inertial Confinement Fusion Target Designs",

Physics of Plasmas 22 (2015) 056304. |

| 74. |

F. Soubiran, B. Militzer,

"Hydrogen-Water Mixtures in Giant Planet Interiors Studied with Ab Initio Simulations",

J. High Energy Density Physics 17 (2015) 157. |

| 73. |

K. Driver, B. Militzer,

"First-principles simulations and shock Hugoniot calculations of warm dense neon",

Phys. Rev. B 91 (2015) 045103. |

| 72. |

S. Wahl, B. Militzer,

"High-temperature miscibility of iron and rock during terrestrial planet formation",

Earth and Planetary Science Letters 410 (2015) 25. |

| 71. |

Y. Lin, R. E. Cohen, S. Stackhouse, K. P. Driver, B. Militzer, L. Shulenburger and J. Kim,

"Equations of state and stability of MgSiO3 perovskite and post-perovskite phases from quantum Monte Carlo simulations",

Phys. Rev. B 90 (2014) 184103, available on the archive. |

| 70. |

H. F. Wilson, B. Militzer,

"Interior phase transformations and mass-radius relationships of silicon-carbon planets",

Astrophys. J. 973 (2014) 34. |

| 69. |

F. Gonzalez-Cataldo, H. F. Wilson, B. Militzer,

"Solubility of silica in metallic hydrogen: implications for the stability of rocky cores in giant planets",

Astrophys. J. 787 (2014) 79. |

| 68. |

P. Kaercher, B. Militzer, H.-R. Wenk,

"Ab initio calculatios of elastic constants in plagioclase feldspars",

American Mineralogist 99 (2014) 2344. |

| 67. |

L. X. Benedict, K. P. Driver, S. Hamel, B. Militzer, T. Qi, A. A. Correa, A. Saul, E. Schwegler,

"A multiphase equation of state for carbon addressing high pressures and temperatures",

Phys. Rev. B 89 (2014) 224109, available on cond-mat. |

| 66. |

S. M. Wahl, H. F. Wilson, B. Militzer,

"Solubility of iron in metallic hydrogen and stability of dense cores in giant planets",

Astrophysical Journal 773 (2013) 95, available on astro-ph. |

| 65. |

B. Militzer, W. B. Hubbard,

"Ab Initio Equation of State for Hydrogen-Helium Mixtures with Recalibration of the Giant-Planet Mass-Radius Relation",

Astrophysical Journal 774 (2013) 148, available on astro-ph. |

| 64. |

B. K. Godwal, S. Stackhouse, J. Yan, S. Speziale, B. Militzer, R. Jeanloz,

"Co-Determination

of Crystal Structures at High Pressure: Combined Application of Theory

and Experiment to the Intermetallic Compound AuGa2",

Phys. Rev. B Rapid Comm. 87 (2013) 100101. |

| 63. |

B. Militzer,

"Equation of state calculations of hydrogen-helium mixtures in solar and extrasolar giant planets",

Physical Review B 87 (2013) 014202. |

| 62. |

H. F. Wilson, M. L. Wong, B. Militzer,

"Superionic to superionic phase change in water: consequences for the interiors of Uranus and Neptune",

Physical Review Letters 110 (2013) 151102, also available on astro-ph. |

| 61. |

S. Zhang, H. F. Wilson, K. P. Driver, B. Militzer,